It is normal to feel some stress during pregnancy. Your body is going through many changes, and as your hormones change, so do your moods.

Too much stress can cause you to have trouble sleeping, headaches, loss of appetite, or a tendency to overeat—all of which can be harmful to you and your developing baby.

High levels of stress can also cause high blood pressure, which increases your chance of having preterm labor or a low-birth-weight infant.1

You should talk about stress with your health care provider and loved ones. If you are feeling stress because of uncertainty or fear about becoming a mother, experiencing work-related stress, or worrying about miscarriage, talk to your health care provider during your prenatal visits.

Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) and Pregnancy

PTSD is a more serious type of stress that can negatively affect your baby. PTSD occurs when you have problems after seeing or going through a painful event, such as rape, abuse, a natural disaster, or the death of a loved one. You may experience:2

- Anxiety

- Flashbacks and upsetting memories

- Nightmares

- Strong physical reactions to situations, people, or things that remind you of the event

- Avoidance of places, activities, and people you once enjoyed

- Feeling more aware of things

- Guilt

PTSD during pregnancy increases the risk of preterm birth and low birth weight. PTSD also increases the risk for behaviors such as smoking and drinking, which contribute to other problems.1

Reducing stress is important for preventing problems during your pregnancy and for reducing your risk for health problems that may affect your developing child. Identify the source of your stress and take steps to remove it or lessen it. Make sure you get enough exercise (under a doctor's supervision), eat healthy foods, and get lots of sleep.

Some women experience extreme sadness and/or anxiety during pregnancy and after giving birth. Many sources of information and support are available to help women experiencing depression or anxiety. Moms' Mental Health Matters explains some signs of these problems and provides an action plan for getting help. Talk to your health care provider if you feel overwhelmed, sad, or anxious. Treatment and counseling can help.

Read the story of how a new mother was affected by depression after giving birth, and the steps she took with her care provider to overcome it.

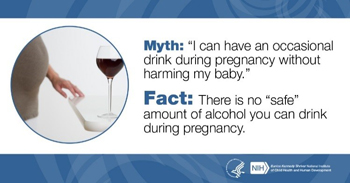

Drinking alcohol, smoking, and taking drugs during pregnancy can increase your child's risk for problems such as fetal alcohol spectrum disorders (FASDs),

Drinking alcohol, smoking, and taking drugs during pregnancy can increase your child's risk for problems such as fetal alcohol spectrum disorders (FASDs),  BACK TO TOP

BACK TO TOP