As we march into spring, the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) and the National Institutes of Health (NIH) are enhancing their coordinated activities to address the problem of maternal morbidity and mortality.

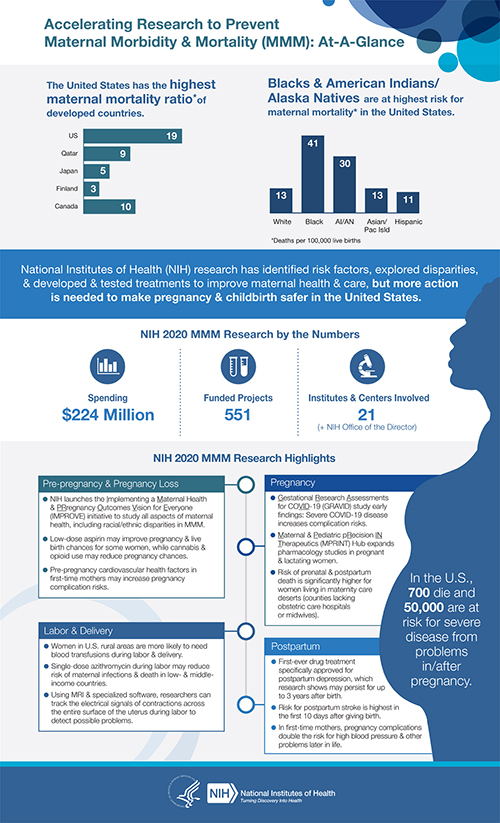

In a wealthy nation like the United States, a healthy pregnancy and childbirth should be the norm, but every 12 hours, a woman dies from complications from pregnancy or giving birth, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Black and American Indian/Alaska Native women are about three times as likely to die from a pregnancy-related cause, compared to white women. Research also shows that up to 60 percent of these deaths are preventable.

The Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) along with the Office of Research on Women’s Health (ORWH) and the Office of the NIH Director, is co-leading the Task Force on Maternal Mortality. Our goal is to fund research that will reduce the rates of life-threatening complications during pregnancy, labor and delivery, and the postpartum period. The task force is developing two initiatives that NIH Director, Francis Collins, M.D., will present to an NIH-wide meeting this month:

- A community-based participatory research project that addresses equity in care

- A project to identify biomarkers for risk of morbidity and mortality during and after pregnancy

In addition, the Surgeon General’s office is working on an action plan on maternal health to identify programs in states and communities that have successfully reduced rates of maternal morbidity and mortality. NIH will advise the Surgeon General’s office, as well as HHS, on research to inform these plans.

Research Response

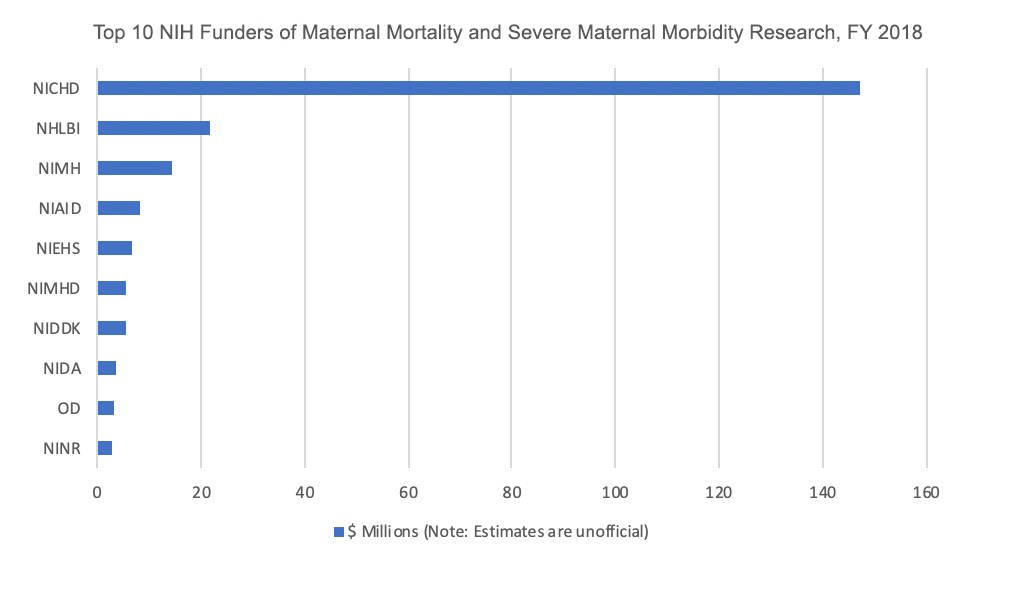

NICHD continues its deep commitment to maternal health, specifically with research to understand and address the increasing U.S. rates of life-threatening complications around pregnancy. NICHD funds more than 65 percent of NIH research on specific conditions related to maternal morbidity and mortality.

Soon, NICHD and other NIH institutes will begin analyzing responses from a recent Request for Information (RFI) that invited comments and suggestions for a proposed research initiative to decrease maternal mortality. The deadline for comments was late February. We look forward to integrating the feedback into our research plans.

Upcoming Workshops

Continuing our collaborative efforts, NICHD and the NIH ORWH are co-hosting a workshop in May to examine Pregnancy and Maternal Conditions that Increase the Risk of Morbidity and Mortality. The two-day workshop, also sponsored by the National Health, Lung, and Blood Institute and NIH’s Office of Disease Prevention, will bring together clinicians and researchers to discuss health conditions that can contribute to a complicated pregnancy, including hypertension, cardiovascular disease and preeclampsia. Registration for this workshop will open at the end of the month. It builds on two NICHD-led meetings in 2019: a community-engagement forum and a scientific workshop focused on health system and structural factors, measurement practices, and social determinants that affect maternal mortality and severe maternal morbidity.

Our 6th annual Human Placenta Project meeting also is scheduled for May. The meeting is an opportunity for scientists, clinicians, and patients to focus on this least understood—and arguably one of the most important—human organs, not only for the health of the woman and her fetus during pregnancy, but also for their lifelong health.

Other Activities

Other current NICHD activities aimed at improving health during and after pregnancy include the following:

- The Task Force on Research Specific to Pregnant Women and Lactating Women (PRGLAC) completed its second phase in February. The task force, established by the 21st Century Cures Act, now is leading an implementation plan for 15 recommendations submitted to the HHS secretary last year.

- PregSource®: Crowdsourcing to Understand Pregnancy is a research project that aims to improve our understanding of pregnancy by gathering information directly from pregnant women through confidential online questionnaires. It is now is available in Spanish.

- Pregnancy for Every Body, is a new initiative that aims to educate plus-size pregnant women about healthy pregnancy and the importance of working with a healthcare provider to develop a pregnancy plan. Despite increased health risks, most plus-size women can have a healthy pregnancy and a healthy baby with regular prenatal care and monitoring by a healthcare provider.

- Birth Settings Study

, supported by NICHD through the National Academy of Sciences, describes the impact of different birth settings

and other social factors on maternal morbidity and mortality.

As I have said in this space before, any maternal death is one too many. I encourage women to get care as early in pregnancy as possible and to discuss their health and habits with their providers. In turn, providers (including non-obstetricians) should take a health history that includes recent pregnancies and listen to women, especially if they have health factors that increase the risk of post-partum complications. NICHD and NIH will continue to advance research to help ensure healthy pregnancies and lifelong wellness.

BACK TO TOP

BACK TO TOP