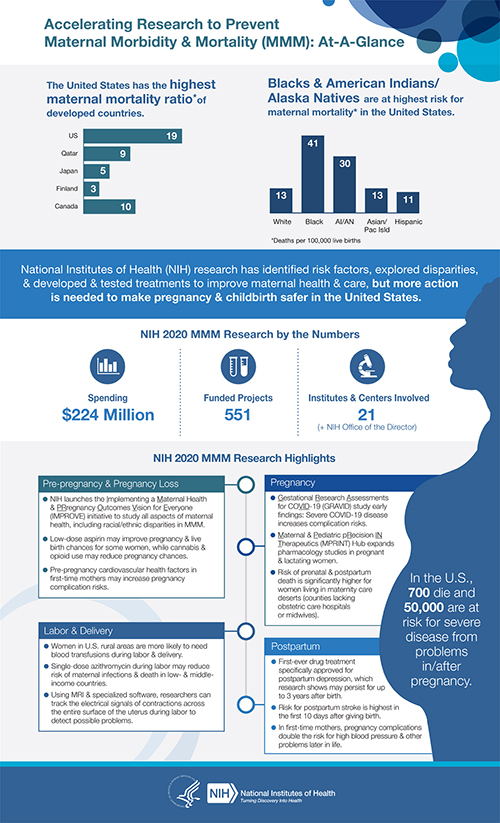

The United States experiences about 700 maternal deaths each year, and American Indian/Alaska Native and Black women are 2 to 3 times more likely to die from a pregnancy-related cause than white women. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimates that two-thirds of maternal deaths may be preventable.1 Thousands more suffer from near misses or severe morbidity.

Maternal health is a priority for multiple NIH institutes that have heavily invested in research to prevent morbidity and mortality and improve overall health. In the past year, with base funding of $223 million,2 NIH has worked across its Institutes, Centers, and Offices (ICOs) and with federal and community partners to support research to reduce preventable causes of maternal deaths and improve health for women, before, during, and after pregnancy. In a year that was dominated by both the COVID-19 pandemic and renewed calls to understand and resolve health disparities and inequities, NIH ensured these challenges were integrated into our efforts to reduce MMM.

Select a link to learn more:

- Generating Evidence to Change Practice and Save Lives through NIH-Supported Research

- Emphasizing Community Engagement

- Pivoting to Address COVID-19

- Looking to the Horizon

- Resources

Generating Evidence to Change Practice and Save Lives through NIH-Supported Research

- Minority women tend to deliver disproportionately in hospitals with lower quality ratings; however, evidence shows that initiatives targeted at quality improvement can substantially improve outcomes.3

- Risk of death during pregnancy and up to 1 year postpartum is significantly elevated among women residing in maternity care "deserts," which are counties that lack hospitals with obstetric care or midwives. Identifying and transporting women with high-risk pregnancies to facilities equipped for specialized care can mitigate MMM risks.4

- Homicide was identified as a leading cause of pregnancy-associated death. Increased contact with the healthcare system during pregnancy provides clinicians with an opportunity to offer potentially life-saving violence prevention services and interventions.5

- Women facing eviction from their homes while they were pregnant are more likely to have poor birth outcomes. Thus, providing housing, social, and medical assistance to pregnant women at risk for eviction may improve infant health.6

Emphasizing Community Engagement

Tackling the challenge of reducing MMM requires strong partnerships with and among local communities and resources, particularly with racial and ethnic minority populations that experience stark health disparities. To that end, several ICOs held community engagement activities to hear first-hand how patient communities can inform future research and what engagement strategies might enhance local efforts to improve maternal health.7,8,9 A common refrain was that research conducted in a community should be developed with and vetted by the community to ensure success and improved outcomes. These engagement activities informed the development of NIH’s IMPROVE (Implementing a Maternal health and PRegnancy Outcomes Vision for Everyone) initiative, which aims to build an evidence base that will improve maternal care and outcomes from pregnancy through one year postpartum.10

Pivoting to Address COVID-19

As COVID-19 ravaged the country in early 2020, research increasingly showed that pregnant women were at higher risk for severe disease, including hospitalization, need for intensive care unit monitoring, and mechanical ventilation. NIH research showed that pregnant COVID-19 patients with severe disease are at higher risk for cesarean delivery, postpartum hemorrhage, hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, and preterm birth.11 These findings come from the Gestational Research Assessments for COVID-19 (GRAVID) study, which evaluated data from more than 1,200 pregnant women at 33 hospitals across the country. Additional research on maternal health related to COVID-19 includes:

- Developing Common Data Elements that can be used in any study involving pregnant women, facilitating data analysis across different research studies12

- Evaluating the effects of remdesivir in pregnant women being treated with the drug for COVID-1913

Looking to the Horizon

NIH is accelerating research on factors that affect pregnancy-related and pregnancy-associated morbidity and mortality to improve care and outcomes. NIH’s Fiscal Year 2020 investments included:

- Supplements to expand existing research projects or support pilot projects for community-partnered research to resolve health disparities, strengthen evidence-based care and improve outcomes, and explore comorbidities to identify preventable risk factors and develop effective early interventions14

- "Addressing Racial Disparities in Maternal Morbidity and Mortality” funding opportunity to support research that tests clinical, social-behavioral, and healthcare system interventions to address racial disparities15 and needs of underserved women16

- Institutional Development Award (IDeA) States, created to expand research and research capability in states that have historically received low levels of NIH funding to address women’s health and maternal and infant morbidity and mortality17; reissued in Fiscal Year 202118

Funding opportunities for Fiscal Year 2021 include:

- IMPROVE initiative supplements to add or expand research focused on the intersection of maternal health, structural racism, and discrimination, and how these were affected by the COVID-19 pandemic19

- Small Business Innovation Research and Small Business Technology Transfer (SBIR/STTR) awards to develop technologies or tools to quantitatively predict or indicate an increased risk for MMM20

- Early Intervention to Promote Cardiovascular Health of Mothers and Children (ENRICH) for testing the effectiveness of an implementation-ready intervention designed to promote cardiovascular health (CVH) and address CVH disparities in marginalized birthing people and children in clinical or community sites21

- Partnership with CDC, the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Trust Fund, and the Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology to create standards to link electronic health record data on maternal and infant health for use in studying the effect of medical conditions and/or interventions on pregnant, postpartum, or lactating women and their infants22

- Interdisciplinary community-engaged research to reduce or eliminate infections and sepsis as MMM causes23

Resources

For additional information on NIH-supported MMM research and funding opportunities:

- NIH MMM Web Portal: https://orwh.od.nih.gov/womens-health-research/maternal-morbidity-and-mortality/welcome

- IMPROVE initiative: https://www.nih.gov/research-training/medical-research-initiatives/improve-initiative

- NICHD MMM website: https://www.nichd.nih.gov/health/topics/maternal-morbidity-mortality

BACK TO TOP

BACK TO TOP