Blocking a key placental defense may limit maternal-fetal transmission of the virus

Hydroxychloroquine, a drug approved by the Food and Drug Administration to treat malaria and certain autoimmune diseases in pregnant women, appears to reduce transmission of Zika virus from pregnant mice to their fetuses, according to a study funded in part by the National Institutes of Health.

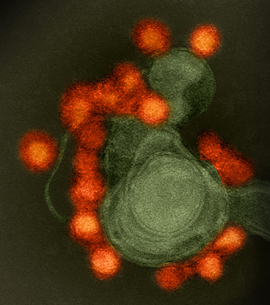

The drug works by inhibiting autophagy, a process by which cells remove toxins and recycle damaged components to generate energy. The researchers show that Zika virus may manipulate this process in the placenta to infect the developing fetus. Their study appears online in the Journal of Experimental Medicine.

“Zika virus infection during pregnancy can lead to a devastating array of birth defects, including microcephaly, abnormal reflexes, epilepsy, and problems with vision, hearing and digestion,” said Catherine Y. Spong, M.D., deputy director of NIH’s Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD), which funded the work. “This study suggests that treating Zika-infected pregnancies with autophagy-inhibiting drugs may lower the risk of these abnormalities, but more research is needed to confirm these findings.”

Previous research has established that autophagy plays an important role in the placenta’s defense against bacteria and other disease-causing agents. In the current study, NICHD-funded researchers led by Indira U. Mysorekar, Ph.D., at the Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, demonstrate that Zika virus infection activates autophagy in lab cultures of human placental cells and in the placentas of mouse models of Zika virus transmission. They then show that, when infected with Zika, pregnant mice lacking an essential autophagy gene called Atg16l1 have significantly lower levels of detectable virus and less placental and fetal damage, compared to Zika-infected pregnant mice who have the gene.

“These results led us to reason that an existing drug that blocked autophagy and could be administered during pregnancy might reduce vertical transmission of Zika virus,” said Dr. Mysorekar.

To test their hypothesis, the researchers administered hydroxychloroquine, an FDA-approved drug known to inhibit autophagy, to Zika-infected pregnant mice. Consistent with the results seen in mice who lacked the Atg16l1 gene, mice treated with hydroxychloroquine have lower levels of detectable virus in their placentas and less placental damage, compared to untreated mice. The treatment also restricts Zika infection in the fetal head and leads to a larger fetal body size, suggesting that the drug limits cross-placental transmission of the virus.

“Our findings indicate that pharmacological inhibition of autophagy warrants evaluation in preclinical studies and eventually in human trials to further define its effects on Zika congenital disease,” added Dr. Mysorekar.

The study received additional funding from the Burroughs Wellcome Fund, the March of Dimes and NIH’s National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

Reference

Cao B, et al. Inhibition of autophagy limits vertical transmission of Zika virus in pregnant mice. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2017;

###

About the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD): NICHD conducts and supports research in the United States and throughout the world on fetal, infant and child development; maternal, child and family health; reproductive biology and population issues; and medical rehabilitation. For more information, visit NICHD’s website.

About the National Institutes of Health (NIH): NIH, the nation's medical research agency, includes 27 Institutes and Centers and is a component of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. NIH is the primary federal agency conducting and supporting basic, clinical, and translational medical research, and is investigating the causes, treatments, and cures for both common and rare diseases. For more information about NIH and its programs, visit http://www.nih.gov.

BACK TO TOP

BACK TO TOP