Meredith Carlson Daly: Welcome to Milestones, a podcast featuring research and insights on child health and human development.

I am your host, Meredith Carlson Daly.

Today we're speaking with Dr. Marian Willinger who oversees NICHD's research programs on Sudden Infant Death Syndrome or SIDS, stillbirth, and infant health. Dr. Willinger is an expert on SIDS and was instrumental in the launch of NICHD's Back to Sleep campaign in 1994. This awareness campaign, now called Safe to Sleep, has been widely credited with reducing the rate of SIDS-related deaths in the United States by more than half.

Dr. Willinger, thanks for joining us.

Dr. Willinger: You're welcome.

Ms. Daly: Also with us today is my colleague Lorena Kaplan, who leads our Safe to Sleep campaign. Lorena, thanks for joining us.

Lorena Kaplan: Thanks for having me.

So, Dr. Willinger, this is a momentous occasion. You are retiring after nearly 30 years of directing research. You leave behind a legacy of tremendous progress in our understanding of SIDS and the great accomplishment of playing a central role in helping to reduce SIDS rates in the country. Can you rewind and reflect a little on how the Back to Sleep campaign started in 1994 and the collaborative effort involved in launching it?

Dr. Willinger: Well, in 1991, the American Academy of Pediatrics formed a task force on sudden infant death syndrome and sleep positioning because there were a number of studies in Australia and New Zealand, Great Britain that were showing that sleeping on your stomach was associated with an increased risk for SIDS and also these countries based on those results were launching their own campaigns to place babies on their sides or backs to sleep to reduce SIDS risk.

As a result, the NICHD, we had no real research to support this here in the United States, this was all based on overseas information and there was a lot of uncertainty about how it would apply to the U.S. And in 1992, the American Academy of Pediatrics was planning to release a recommendation that infants should be placed on their sides or back to sleep to reduce SIDS risk. I went to Australia and met at a SIDS meeting with all the leaders of the SIDS research and campaigns oversees to find out what we needed to get the research information to make it applicable here in the United States.

We met with the American Academy of Pediatrics and came up with a research agenda. They released their recommendation in 1992, and in the interim, we developed studies to one, find out what our baseline information was, how babies were placed to sleep and see if that changed as the recommendation was released; and also track it to see what happened with SIDS rates over time. We, also, because there was concern that babies would aspirate on their backs, because that was the reason that it was recommended that babies be placed on their stomach, we funded some analyses of prospective cohorts in Australia, and in Britain where we knew the sleep position was changing and we could look and see if there were any adverse health effects of placing a baby on their sides to sleep. And as the data came in, we saw that with the campaigns overseas, the SIDS rates were dropping dramatically. We also got back information that it appeared there were no adverse health effects of side or back sleeping.

Ms. Daly: You still were a little skeptical?

Dr. Willinger: Yes, I was in the beginning when the recommendation was released, but over the two years between 1992 and early or late 1993, we were getting all this information that said this thing is working and even though our SIDS rates were much lower here and we had a much higher proportion of babies on their stomach, we felt it wouldn't hurt, it made sense to support the recommendation and what we probably really needed was a national public education campaign because there were no educational materials that went along with the academy recommendation.

So, we formed a coalition between the American Academy of Pediatrics, the United States Public Health Service (PHS) and the two professional SIDS organizations ASIP and the SIDS Alliance to think about what we would do to launch a national public education campaign. We also reinvigorated the US Interagency Committee on Sudden Infant Death Syndrome to get all the agencies together and ready.

Then, in January 1994, we held a conference where we invited all the interested parties, members of the pediatric community, the SIDS community, the federal partners to review all the evidence that was out there to date, including, we invited international researchers to come and present. There was a consensus that the federal government should be involved in a national public health campaign. We then informed the assistant secretary of health, got the surgeon general on board and launched our campaign in June of 1994.

Ms. Daly: So how did you come up with Back to Sleep.

Dr. Willinger: That was the campaign slogan I think in Britain. So, we adopted an international slogan, if I recall. Plus, we used the Department of Census for the 1-800-505-CRIB hotline. All of that was put together literally in less than a year.

Ms. Daly: That's amazing. In 6 months, right?

Dr. Willinger: yes. Really it was very quick.

Ms. Daly: Wasn't it launched in June of 1994?

Dr. Willinger: That's right

Ms. Kaplan: Who at NICHD led the effort, in addition to you, of course.

Dr. Willinger: Well Dr. Duane Alexander, who was our (NICHD) Director at the time was really key and a leader from the moment that he learned about the formation of the AAP taskforce starting in March of 1992. He was determined that not only would we have a research agenda to help support the evidence and move it forward here in the United States, but also that the NICHD would lead the PHS effort in the Back to Sleep campaign and he was responsible for making sure that this was a high priority for the institute and putting the resources available for it.

We also launched some new studies here in the United States, especially in our high-risk populations. So, in collaboration with CDC (Centers for Disease Control) we launched the Chicago Infant Mortality study, which focused primarily on Cook County and the African-American community; we launched the Aberdeen Area Indian Health Service Infant Mortality Study in collaboration with CDC and the Indian Health Service in the Northern Plains Tribal communities.

And then we had another case-control study launched out in California to look at the risk factors post the implementation of Back to Sleep and we also launched a prospective study in New England, in Boston, and in Ohio, to get more information on the health effects of changes in sleep position. And that study actually found that babies were less likely to have colds and ear infections if they were placed on their backs at no increased risk of aspiration. And as the data came in, it was clear that putting a baby to sleep on their backs was extremely safe and actually as we've seen over the years, the sudden infant death syndrome rate dropped 50 percent.

Ms. Daly: Dr. Willinger, you are a parent, grandparent. When you reflect and look back, what is the greatest impact of this campaign.

Dr. Willinger: I guess the greatest impact is that there are fewer parents that are going to feel the terror and the loss and the grief of a baby who dies from SIDS because these babies, what's made this so difficult to study is that they show no evidence of illness. I mean, SIDS is basically a diagnosis of exclusion when a full autopsy has been investigated and review of the medical history has been done and no other cause is found, then the baby is given a diagnosis of Sudden Infant Death Syndrome.

So that for these families, you know here they think they have a healthy baby. And then one morning or after a nap, the baby is gone. The tremendous grief, tremendous guilt, you know, what could I have done? Did I miss something? All of that I mean it really, it just tears families apart. So, I think if I could have helped in that as a parent, that is a wonderful thing.

Ms. Kaplan: What do you think, building on all of the progress, that 50-percent reduction, what do you think are the biggest opportunities or challenges for the Safe to Sleep campaign?

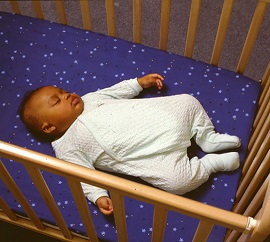

Dr. Willinger: Well, I think the biggest challenges for the Safe to Sleep campaign is that there are still people who do not implement safe-sleep practices. There are still some doctors or nurses who even though it's not a large percentage who still are not counseling and advising parents. I think while we've seen a large reduction in stomach and side sleeping, and a good percentage of babies being placed on their back. We still have too many babies who are sharing a bed with adults and that's a very unsafe sleep practice and babies who are placed to sleep with soft bedding, quilts, comforters or blankets under them because parents think that that's comfortable for them and it's actually very unsafe. So, I think, we haven't made enough of a dent in those two unsafe sleep practices. There is controversy around bed sharing because women who breast feed, they bring their babies into bed to breastfeed. It's important for them to remember that when they're finished breastfeeding that the baby needs to go back to their own safe-sleep place, either a co-sleeper attached to the bed, which the Consumer Product Safety Commission has looked at, or a bassinet, a free-standing bassinet, or a cradle. Keeping the baby in the same room. There are many epidemiologic studies that have shown reduces the risk by 50-percent. So, you want to have in the same room, but in a separate safe-sleep place.

Dr. Willinger: Well, I think the biggest challenges for the Safe to Sleep campaign is that there are still people who do not implement safe-sleep practices. There are still some doctors or nurses who even though it's not a large percentage who still are not counseling and advising parents. I think while we've seen a large reduction in stomach and side sleeping, and a good percentage of babies being placed on their back. We still have too many babies who are sharing a bed with adults and that's a very unsafe sleep practice and babies who are placed to sleep with soft bedding, quilts, comforters or blankets under them because parents think that that's comfortable for them and it's actually very unsafe. So, I think, we haven't made enough of a dent in those two unsafe sleep practices. There is controversy around bed sharing because women who breast feed, they bring their babies into bed to breastfeed. It's important for them to remember that when they're finished breastfeeding that the baby needs to go back to their own safe-sleep place, either a co-sleeper attached to the bed, which the Consumer Product Safety Commission has looked at, or a bassinet, a free-standing bassinet, or a cradle. Keeping the baby in the same room. There are many epidemiologic studies that have shown reduces the risk by 50-percent. So, you want to have in the same room, but in a separate safe-sleep place.

Ms. Daly: There still so much more to learn about SIDS from a research angle. I know your background is in neuropathology and you've made connections with brain abnormalities in SIDS cases. Where do you see this field going? Where do we need to focus in the future?

Dr. Willinger: Well I think it's really important, the brain abnormality that's been known for a longest time in a large proportion of SIDS cases is abnormalities in the part of the brain stem that controls arousal, breathing, heart rate during sleep. But now there's been some new findings of abnormalities in the hippocampus of some babies. So, what we really need to understand is how are those two abnormalities related. Do they occur in the same babies? Are these different babies that sort of lead down to the same ultimate pathogenic pathway? Are the pathways different?

I think the other thing is we need to be able to identify babies who are truly at increased risk. SIDS is rare and right now the way we're handling intervention is to say all babies need to be placed to sleep on their backs.

But even babies who sleep on their backs are dying. So, we need to be able to find out what are the physiological parameters that identify a baby at highest risk and once we understand that we also may be able to develop more specific and targeted therapeutics. So, I think that's the direction that we're going in.

Ms. Daly: And just to switch topics a little bit because I know that stillbirth was also quite a priority of yours. Where do we need to focus in terms of stillbirth?

Dr. Willinger: Well stillbirth there are over 26,000 stillbirths in the United States each year, so it's equivalent to the number of infant deaths. But it's a highly understudied area. NICHD started in 2003, having a meeting and publishing a research agenda. We had the stillbirth collaborative research network, which has done a lot of work in that arena. We need to do more. Stillbirths are heterogenous in their cause. There are early stillbirths that are more likely related to causes of periviable death, very early prematurity. Then there are late stillbirths, which are more likely to be unexplained after a big investigation and all different medical and obstetrical causes in between. We've made a lot of progress in understanding risk factors and some of the medical etiology, we need to continue to understand what the causes of stillbirth so that there are better obstetrical interventions to prevent them.

Ms. Daly: And when you say early, give us the parameters.

Dr. Willinger: So, the early is 20-23 weeks. So, that's the periviable period. And the babies are dying from early premature labor for the most part.

Ms. Daly: And then just looking back since so much of your career has been here at NICHD and at NIH. What will you miss? What will be the hardest part about not coming to NIH every morning?

Dr. Willinger: I think I'm going to miss the people I have worked with. The people that I've worked with here at NIH here are some of the most dedicated, passionate people I've ever met and also the brightest. They really care. They want to be able to prevent suffering. I feel that I've had a special connection with them because we had a similar goal. I think it's wonderful to have an opportunity to be able to be with people who share your passion.

Ms. Daly: Well, we've been speaking with Dr. Marian Willinger who led the NICHD's research programs on SIDS, stillbirth and infant health for almost 30 years. Thanks also to my colleague Lorena Kaplan, who leads NICHD's Safe to Sleep campaign.

Thank you all for listening to another edition of Milestones.

I'm your host Meredith Carlson Daly.

BACK TO TOP

BACK TO TOP