Credit: Stock Image

Understanding child development and behavior is a core focus of NICHD’s research mission. We study early learning, learning disabilities, and conditions such as attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Although ADHD is not a learning disability, it can still affect learning, behavior, and school achievement.

Some recent NICHD-funded research findings on ADHD include the following:

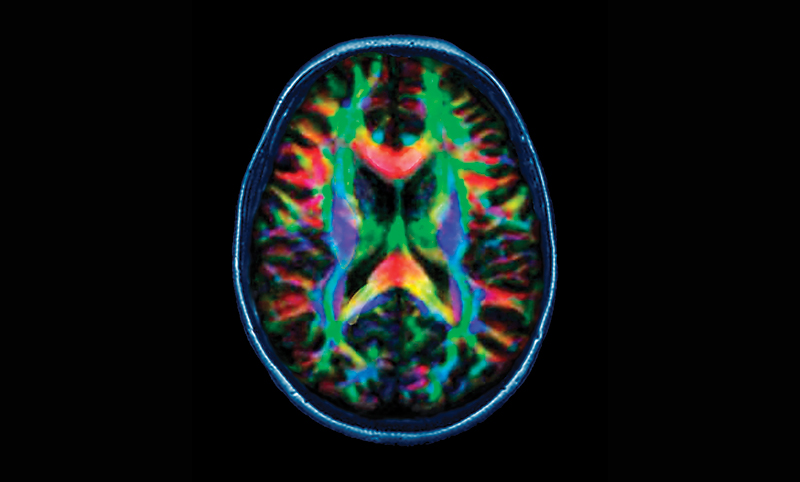

- In the first comprehensive examination of structural brain changes in preschoolers with signs of ADHD, researchers found that significant differences in brain structure can be observed in 4-year-olds who have ADHD symptoms. NICHD-funded researchers at the Kennedy Krieger Institute in Baltimore used high-resolution scans to compare the brains of 52 children with ADHD symptoms to those of 38 kids without symptoms. Previous studies documented brain differences in adolescents with ADHD, but this was the first study to examine brain differences in preschoolers. Learn more about the study.

- NICHD-funded research suggests that a traumatic brain injury during early childhood may be linked to ADHD several years after the injury. Previous research showed that children as young as 3 years old with a history of brain injury have a higher risk of developing attention problems. This study, which followed children for up to 10 years after their initial brain injury, found ADHD symptoms may develop years later. Most of the children developed secondary ADHD within 18 months of their injury, but some didn’t start showing symptoms for several years. Learn more.

- NICHD supports the Video Interaction Project (VIP) , a socio-emotional intervention project that focuses on parent-child interactions. The project occurs within a primary care setting, where a trained provider assists parents with pretend play, shared reading, and daily routines to improve their child’s behavior, development, and school readiness. As part of VIP, researchers videotaped parents reading to their children for about 5 minutes and then reviewed the recording with parents, emphasizing the positive responses from their children. Previous research showed that parents who saw their children’s positive responses were motivated to continue reading and playing together. Newer data shows the intervention also improves child behavior. Three-year-olds who received the intervention were significantly less likely to be aggressive than 3-year-olds in a control group who didn’t interact with their parents. A follow-up study of the same group of children showed that improved behavior continued to almost school-age. Read more about these findings.

- Finding ways to help kids with ADHD focus and learn is a core aspect of NICHD research. A study led by NICHD-funded researchers at the University of California, Irvine, School of Medicine, found that therapy dogs could be an effective option. Among children ages 7 to 9 who were diagnosed with ADHD and had no prior history of medication for the condition, therapy dogs were effective at reducing overall severity of ADHD symptoms after 12 weeks. In addition, children with therapy dogs showed better attention and social skills after only 8 weeks. Learn more about the findings.

- ADHD is a common diagnosis not only for young children, but also among adolescents. A group of NICHD-supported researchers examined the effect of frequent digital media use on the timing of ADHD symptom onset in high school students. A total of 2,587 students from 10th through 12th grades in 10 Los Angeles County high schools completed surveys about their digital media use over a week-long period. The findings showed teens who frequently engaged in digital media use—such as playing video games and checking social media multiple times a day—were more likely to develop ADHD symptoms. These findings could help healthcare providers fine-tune treatment recommendations for teens with ADHD. Read more about this research.

- Although a specific cause for ADHD is unknown, research shows that multiple contexts contribute to the condition. For example, one NICHD-funded study suggested that high blood lead levels in early childhood may increase the risk of ADHD. Researchers analyzed data from 1,479 mother-infant pairs recruited for the study at Boston Medical Center beginning in 1998 and followed the families until the end of 2016. The study found that boys with high blood lead levels were more vulnerable to ADHD than girls, but the risk to boys was reduced by half if the mother reported low stress levels during pregnancy. The findings offered clues to sex differences in ADHD and opportunities for early risk assessment. Learn more about the study.

Understanding conditions that affect child development, such as ADHD, is key to helping ensure that children grow up healthy. NICHD relies on its different organizational units, including the Child Development and Behavior Branch, to support research initiatives and research training to help promote the best outcomes for children.

BACK TO TOP

BACK TO TOP