Credit: Claire Le Pichon, Ph.D.

Before joining NICHD as a tenure-track investigator in 2016, Claire Le Pichon, Ph.D., had lived on three continents, taught science in a prison, and skipped a traditional postdoctoral fellowship in favor of working in the biotechnology industry. Her breadth of experience helps her lead, mentor, and motivate the diverse group of fellows and students working in the Unit on the Development of Neurodegeneration within NICHD’s Division of Intramural Research. The lab aims to understand how different types of neurons respond to axon injury—damage to the part of the nerve cell that enables it to communicate with other neurons—and the role of these responses in neurodegenerative diseases, such as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS).

“Watching Claire build up her lab has taught me lessons I hope to carry over to my own lab one day,” says Mor Alkaslasi , a Brown University student conducting her doctoral research in the Le Pichon lab through NIH’s Graduate Partnerships Program, “including how to prioritize and work efficiently, keep up with the latest techniques and technology, and create a friendly and collaborative lab environment.”

Mentoring the next generation of scientists is one of Dr. Le Pichon’s passions. “Each mentee needs something different from you. It’s not one-size-fits-all,” she observes. “Realizing that I had to adapt to their individual work styles was an important moment for me.” Adaptability has been a common theme throughout Dr. Le Pichon’s career. Her flexibility and ability to keep an open mind helped her transition from the team-science environment of industry to an independent lab, balance her career ambitions with motherhood, and face the challenges posed by the COVID-19 pandemic.

An International Upbringing

Dr. Le Pichon was born in the United Kingdom (U.K.) to a French father and a mother from Hong Kong. During her childhood, the family moved from London to New York City for her father’s job in finance. When Dr. Le Pichon was in high school, they relocated to Hong Kong to support her mother’s career transition from lawyer to judge, and to be closer to her aging grandparents.

Although neither were scientists, both of Dr. Le Pichon’s parents helped influence her career choices. “My father was a good example to me of how fluid a career could be,” Dr. Le Pichon says. He started as a schoolteacher and transitioned to banking when he became a parent. When the family moved to Hong Kong, he went back to school in his 50s to earn his Ph.D. in colonial history, and later returned to teaching as a professor at the Sorbonne University in Paris. Her mother, who was very ambitious in her legal career while also attentive to the family, served as a good example for Dr. Le Pichon’s efforts to balance running a lab with being a mom.

Developing an Interest in the Neurosciences

School remained a constant during Dr. Le Pichon’s upbringing. She and her sister always attended French international schools, which followed a consistent curriculum. She enjoyed many subjects, including music and photography, which both remain hobbies today. In high school, she developed her love for biology and remembers being particularly fascinated by learning about the coordinated response of immune system cells to fight infection.

Dr. Le Pichon returned to the U.K. for her undergraduate work, attending Cambridge University to study the natural sciences. She was drawn to disease biology but quickly realized that she was not interested in pursuing a medical degree. She completed the equivalent of a major in the pathology department.

“I was always fascinated by the unknown,” Dr. Le Pichon says. “I hadn’t completely caught the research bug at the undergraduate stage, but I was intrigued enough to apply to graduate programs.” She ultimately chose the Ph.D. program in biological sciences at Columbia University in New York. The program required students to rotate through several labs before selecting a thesis lab. While Dr. Le Pichon enjoyed the exposure to different types of biological research, she “immediately gravitated toward the neurosciences.”

She joined the lab of Stuart Firestein, Ph.D. , to study olfaction and sensory neurobiology. She was fascinated by how the human nervous system processes information from the outside world to mediate behaviors and how that can go wrong in disease. She notes that Dr. Firestein had an enormous influence on her career, thanks both to his scientific approach and his unique personality. Prior to earning his Ph.D. in neurobiology, Dr. Firestein had a career in theater. “His lab was really diverse, everyone was very motivated to succeed, and it was huge amounts of fun,” Dr. Le Pichon says.

Dr. Firestein pushed his trainees to be independent scientists and come to their own conclusions. Dr. Le Pichon remembers arranging a meeting with him to express her desire to abandon a project that she felt was unlikely to yield meaningful results. Dr. Firestein was supportive, noting that he had felt the same about the project for a few months. Dr. Le Pichon recalls initially feeling shocked: “He had known this was a dead-end for a few months and hadn’t told me?” But ultimately, she was grateful for the opportunity to consider the matter independently, which built confidence in her scientific decision-making.

During her time at Columbia, she also met and married her husband, Alexander Chesler, Ph.D., then also a doctoral student in the Firestein lab.

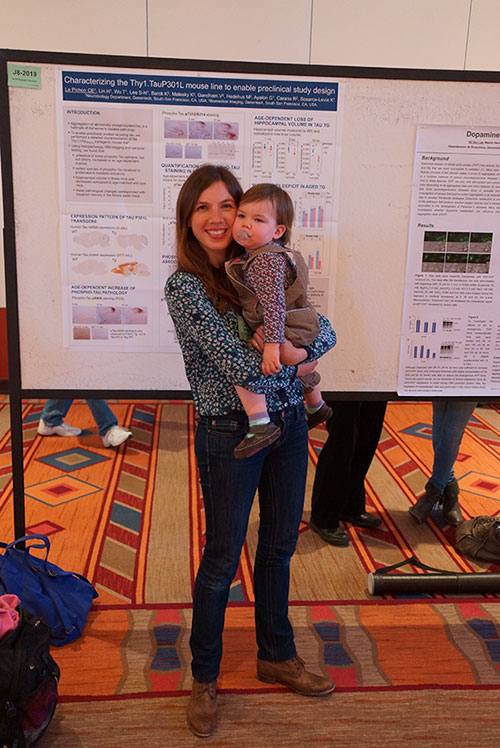

Credit: Claire Le Pichon, Ph.D.

Credit: Claire Le Pichon, Ph.D.

A Circuitous Route to NIH

After receiving her Ph.D. in 2007, Dr. Le Pichon explored alternatives to a traditional career in academia. From 2007 to 2008, she served as a Columbia Science Fellow, wrapping up her projects in the Firestein lab while teaching the university’s science core curriculum to undergraduates. For the Bard Prison Initiative , a program that provides college education to incarcerated people, she adapted the science core curriculum and taught it to women living in a New York City prison. “It was one of the most rewarding experiences,” she recalls. “The students were so motivated.”

At the same time, Dr. Chesler moved to California for a postdoctoral fellowship at the University of California, San Francisco, and Dr. Le Pichon began exploring career opportunities in the Bay Area. She became curious about Genentech, a biotechnology company known for conducting basic science in-house and applying it to drug development, a practice that meshed well with her interest in disease biology. Although she worried that taking a job in industry could close the door to a career in academic science, she felt she would learn and grow from the experience, ultimately deciding she would regret passing up the opportunity. She joined Genentech as a senior research associate in translational neuroscience for neurodegenerative diseases in 2008.

Credit: Claire Le Pichon, Ph.D.

Dr. Le Pichon enjoyed the collaborative, team-based science approach at the company, as well as the exposure to cutting-edge technologies. She learned how to design and lead rigorous preclinical studies. She also began to realize that, to make a meaningful impact on the treatment of neurodegenerative diseases, scientists need to better understand the underlying biology of disease development. This concept motivates her research today.

Drs. Le Pichon and Chesler also welcomed their daughter, now 10 years old, during her time at Genentech. Dr. Le Pichon’s supervisor at the company, Kimberly Scearve-Levie, Ph.D., had two young children and was an inspiring role model for how to balance career and family.

Eventually, family circumstances galvanized another career change when Dr. Chesler accepted a tenure-track position at NIH in Bethesda, Maryland, in 2013. Dr. Le Pichon initially secured a position as a senior research fellow at NIH’s National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. But observing her husband set up his lab, she was impressed by the possibilities offered to NIH’s tenure-track investigators. “You have this amazing opportunity to do fully funded work. You don’t have to stress about applying for grants. You can even make time to work in the lab yourself,” she says. “I thought, ‘I want that job.’”

Not long after the birth of her son, now 7 years old, Dr. Le Pichon began her dream job as a tenure-track investigator at NICHD.

Establishing an Independent Lab

Dr. Le Pichon describes her first year as an independent investigator as an emotional rollercoaster. “Transitioning from working in a team environment to being a lab leader—with all the choices and decisions on my shoulders—was terrifying, but also very exciting because I was able to go in the direction that I wanted,” she says.

She notes that the support of her peers and mentors was critical in helping her through those challenging times. She also felt that her stint working in industry gave her certain advantages. While most new investigators have no prior management experience or training, she managed two direct reports while at Genentech. Her time at the company also helped her develop many of the basic science questions that her lab now seeks to answer, such as how neurons respond to nerve injury and other pathologies.

“Claire has not needed a lot of assistance in establishing herself as a tenure-track investigator,” says Mark Hoon, Ph.D., a senior investigator at NIH’s National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research and one of Dr. Le Pichon’s mentors. “She seems to naturally anticipate what is necessary and get it done.”

Credit: Claire Le Pichon, Ph.D.

With two children and two labs to run in the Le Pichon-Chesler household, balancing family life with career can be a challenge. Sharing the household work is key to keeping life running smoothly, says Dr. Le Pichon, although she acknowledges that an even division of childcare responsibilities is easier now that the children are older and more self-sufficient. She often advises her mentees that there is no “best time” in a person’s career trajectory to start a family. “To a certain extent, you just have to figure it out as you go along,” she says.

Embracing New Technologies

While Dr. Le Pichon was conducting her doctoral research, gene chips became commercially available. These tiny glass slides contain thousands of known DNA sequences, allowing scientists to easily investigate which genes are involved in certain biological processes. Dr. Firestein immediately embraced the technology and had a gene chip custom-made to study olfactory receptors. “As soon as we had that new tool, we could see things that we never could before,” Dr. Le Pichon recalls. “Dr. Firestein’s enthusiasm for adopting new technologies had a huge influence on me.”

More recently, advances in single-cell sequencing have allowed researchers to study differences between cells, identify cell subtypes, and gain insights into how specific cells respond to their environment. Dr. Le Pichon grew interested in seeing how these techniques could be applied to adult spinal cord motor neurons, which are responsible for all types of movement in the body. Although several laboratories were using single-cell sequencing to study spinal cord cells, their published reports presented little to no data on motor neurons. The Le Pichon lab decided to take on the difficult task of analyzing this cell population.

Isolating and sequencing spinal cord motor neurons is technically challenging, due in part to their rarity among spinal cord cells and their large size. Using a genetic strategy, the Le Pichon lab and collaborators were able to mark and isolate the nuclei of motor neurons in the adult mouse spinal cord. Single-cell RNA sequencing of these nuclei revealed 21 subtypes of motor neurons in discrete areas throughout the spinal cord.

While previewing some of these data at the 2020 Packard Meeting on ALS research, Dr. Le Pichon learned that a laboratory at Stanford had been using an analogous method to sequence adult mouse spinal cord motor neurons. Their data correlated almost perfectly with the Le Pichon lab’s findings. While the two labs separately published their work, they combined their data into a freely available online adult mouse motor neuron atlas . The combined work offers insight into how these neurons control movement, how they contribute to the functioning of organ systems, and why some are disproportionately affected in neurodegenerative diseases.

A Happy Lab

According to mentor Dr. Hoon, one of Dr. Le Pichon’s major strengths is her ability to motivate the diverse group of trainees in her lab. “Her team is happy, while at the same time doing good work, which shows she has created a great atmosphere in her lab,” he notes.

Ms. Alkaslasi agrees, noting that “the fun, energetic environment” she experienced during her rotation in the Le Pichon lab helped convince her that it was the right fit for her doctoral research. “Claire is an amazing mentor. She gives her trainees opportunities to grow, guides us to improve ourselves as scientists, encourages work-life balance, and spreads her excited curiosity about science,” she says. “I walk out of my weekly meetings with Claire excited about the science we’ve discussed and the experiments I’m about to do—from what I hear, that’s not common in graduate school.”

Credit: Claire Le Pichon, Ph.D.

The curiosity-driven atmosphere extends beyond the walls of the Le Pichon lab. Dr. Le Pichon’s other strengths include her willingness and ability to collaborate with other researchers, notes Dr. Hoon. “Claire has shown me that collaboration is a productive and useful way to get more research done,” he says.

“I recognized the power of collaborative science when I was at Genentech,” says Dr. Le Pichon. “The thing I enjoy most about working at NIH is the wonderful community of colleagues I get to interact and collaborate with. The cross-pollination of ideas and the sharing of expertise really helps the science advance more quickly.”

For example, the Le Pichon group worked with NICHD’s Timothy Petros, Ph.D., and his lab on the adult mouse motor neuron atlas. They also collaborate with research groups across NIH studying sensory neuron injury, including those led by Nicholas Ryba, Ph.D., Dr. Chesler, and Yasmine Belkaid, Ph.D. Additionally, they are working with the laboratories of Ariel Levine, M.D., Ph.D., on spinal motor neurons and Carsten Bönnemann, M.D., and Teresa Dunn, Ph.D. , of the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, on a childhood form of motor neuron disease.

Looking Toward the Future

The major goal of the Le Pichon lab is to understand how different types of neurons cope with stress or injury across the lifespan. By the time many neurodegenerative diseases are diagnosed, a large percentage of neurons has already been lost. Developing more effective treatments for these diseases requires an understanding of the biology underlying disease onset and progression.

The COVID-19 pandemic slowed the lab’s progress toward this goal, but did not douse their commitment to the science. With strict limits on in-person staffing, they had to reduce their mouse colony size and delay numerous experiments. But, in Dr. Le Pichon’s opinion, the lack of casual daily interactions in the lab had the greatest negative impact. “We didn’t have the types of interactions that really drive the science forward, like looking down the microscope together,” she says. “Lab members would take pictures and share them with me on Zoom, but I don’t know what else they saw that they didn’t take pictures of. I really missed that kind of in-the-lab mentoring.”

However, the hybrid work environment imposed by the pandemic had at least one silver lining. The lab began hosting group Zoom meetings with non-NIH investigators who shared their research interests. “Before the pandemic, we didn’t realize how easily we could meet virtually across different cities and time zones. We have started some new collaborations as a result. It’s been a really good thing,” says Dr. Le Pichon. As the lab returns to pre-pandemic staffing levels, they intend to continue these virtual meetings.

Much like the iterative process of scientific research itself, Dr. Le Pichon views her leadership of the Unit on the Development of Neurodegeneration as a work in progress. “I try to tailor my approach to each mentee’s needs and goals. One of the first things I learned when I started my lab—and am continuing to learn—is how different each trainee is, including in terms of what they need from me. And what is cool is how this evolves over time as they grow and mature as scientists,” she says. “Every year I meet with each trainee to reflect together: What can you do better to achieve your future goals? What can I do better to help you achieve that?”

BACK TO TOP

BACK TO TOP