Credit: NIH/Chia-Chi Charlie Chang

Veronica Gomez-Lobo, M.D., director of Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology (PAG) at NICHD, began her career as a clinician focused on caring for underserved populations. Taking advantage of interesting opportunities led her to become involved in medical education, and later, in scientific research.

Today, her position combines her skillsets in research, teaching, and clinical care. She leads a robust NICHD research program exploring fertility preservation in special populations, rare gynecologic conditions, and other issues in pediatric gynecology. She also directs a PAG fellowship program and cares for patients at MedStar Washington Hospital Center (MWHC) and Children’s National Health Systems.

Her colleagues and trainees describe her as an expert surgeon, a leader in developing and advancing PAG as a subspeciality, a compassionate caregiver, and an excellent mentor.

“She didn’t take a traditional route to get to where she is today, and I think that’s really important,” says Jacqueline Yano Maher, M.D., a staff clinician in NICHD’s PAG division and director of the female fertility preservation program at Children’s National Hospital. “Her career illustrates that there are many paths to success within medicine and research.”

An Early Interest in Medicine

Although Dr. Gomez-Lobo does not recall what originally sparked her interest in a medical career, it has been her focus since childhood. “In first grade, they asked us what we wanted to be when we grew up. I said I wanted to be a nurse,” she says. “By age 12, I was saying, ‘I want to be a doctor.’”

Dr. Gomez-Lobo’s early years were divided between Germany, where her father was conducting his doctoral work in philosophy, and her parents’ native Chile. The family was living in Chile in 1973, when a coup d’état ended democratic rule and established a military dictatorship. They left shortly after and eventually settled in the United States when Dr. Gomez-Lobo was in sixth grade. Her father secured a position as a philosophy professor at Georgetown University, while her mother concentrated on raising Dr. Gomez-Lobo and her three siblings.

After high school, Dr. Gomez-Lobo attended Georgetown University. During her sophomore year, she was accepted to Georgetown’s School of Medicine through the university’s Early Assurance Program, which allowed her to spend her junior year abroad studying at the Frei Universität in Berlin, Germany. She received her B.S. in chemistry and began medical school in 1985.

It was during medical school that she developed a strong interest in caring for underserved populations. She also met her future husband, fellow student Thomas Fishbein, M.D., who was assigned to the neighboring cadaver in the lab. After receiving her M.D. in 1989, she completed an internship in obstetrics and gynecology (OB/GYN) at Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia, followed by a residency at Tufts Medical Center in Boston. Dr. Gomez-Lobo and Dr. Fishbein married during her third year of residency.

An Indirect Path to a Research Career

After residency, Dr. Gomez-Lobo started her “dream job” providing OB/GYN care at Cambridge Hospital, a small public hospital in Massachusetts. She continued her work caring for underserved groups for the next several years, moving a few times to accommodate Dr. Fishbein’s blooming career as a transplant surgeon. They also began growing their family, welcoming their first daughter—now 28 years old—during Dr. Gomez-Lobo’s second year as an attending physician. In the coming years, they had another daughter and a son, now 25 and 21, respectively.

Raising three children in a two-physician household meant that my career was not always something I could pursue fully,” says Dr. Gomez-Lobo. “But I have accomplished a lot. The important thing is to get to a place where you’re excited about what you’re doing.”

About a decade into her career as a practicing OB/GYN, Dr. Gomez-Lobo began to gravitate toward serving pediatric and adolescent populations. Establishing herself in the nascent PAG subspeciality entailed learning many new techniques, including pediatric surgery. Accustomed to the female-dominated field of OB/GYN, she experienced a bit of culture shock when she started working with male-dominated surgical teams. Although she did not experience overt sexism, she remembers finding it difficult to balance the need to be assertive with feelings of being judged negatively. She also recalls feeling doubts and insecurities about her abilities. “It was tough. You make mistakes. You sometimes feel humiliated,” she says. “But I just kept talking to other clinicians, asking questions, and learning. And that’s how I got across those hurdles.”

Dr. Gomez-Lobo credits following paths that interest her with helping her career evolve in other ways, too. While working at St. Luke’s Roosevelt Hospital in New York City, she accepted an invitation to serve as its residency director. She then served in the position for eight years, at St. Luke’s Roosevelt and Mount Sinai, where she discovered a love for training the next generation of clinicians—a passion that remains central to her work today.

In 2003, Dr. Fishbein was recruited to Georgetown, and the family relocated to Washington, D.C. Dr. Gomez-Lobo recalls that she initially struggled to find a job where she could both teach and care for those with the most need. At first, she divided her time between Unity Health Care, a large network of community health centers, and MWHC. About a year after arriving in the nation’s capital, she met a prominent employee of Children’s National Hospital at a social event. He noted that Children’s National—which is located next door to MWHC—would benefit from the expertise of a pediatric gynecologist and invited her to come consult once a month.

Over the next few years, Dr. Gomez-Lobo built a large PAG program at Children’s National, where she and her NICHD team continue to provide clinical care today. In 2010, she launched a PAG fellowship program that now involves faculty from NICHD, Children’s National, and MWHC. The first fellow in the program, Lauren Damle, M.D., found the experience so compelling that she decided to remain at MWHC and Children’s National after her fellowship to continue working with Dr. Gomez-Lobo.

“Dr. Gomez Lobo taught me not only clinical medicine, but also invaluable lessons about how to care for patients and their families on an emotional level,” says Dr. Damle, now an attending physician and assistant professor of OB/GYN at Georgetown University School of Medicine. “I have never met a physician who is more dedicated to their patients’ overall well-being than Dr. Gomez-Lobo.”

As part of her efforts to advance the field of PAG, Dr. Gomez-Lobo also became more involved in scientific research. As president of the North American Society for Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology (NASPAG) in 2016 and 2017, she established a research committee

to foster high-quality research among NASPAG members and create opportunities for collaboration. The committee now funds small research awards, has a mentorship program for young investigators, and further supports research efforts through efforts such as issuing letters of support or disseminating surveys through the membership. Dr. Gomez-Lobo also established an ongoing Fellows Research Consortium

to enable fellows to work collaboratively with peers and leaders to conduct multi-center research.

Finding a Scientific Niche

Dr. Gomez-Lobo’s early research projects focused on the health of women who had received solid organ transplants, such as livers or kidneys. She describes her involvement in this research as “very opportunistic”—as she was providing clinical care to these women, she saw an opportunity to learn more about a population that had not been well-studied. She started with survey-based qualitative research and then moved to more complex projects, such as studying immune responses to the human papillomavirus vaccine among adolescent transplant recipients. “Don’t think about starting too big,” she now counsels early-career scientists. “Start simple and build on those steps.”

Dr. Gomez-Lobo’s early research experiences highlighted the need for more in-depth research on how various health conditions impact women’s and girls’ health. She has since contributed to numerous research advances and co-authored more than 100 peer-reviewed publications. “But what I’m most proud of is where I am now and the steppingstones that my team is creating,” she says.

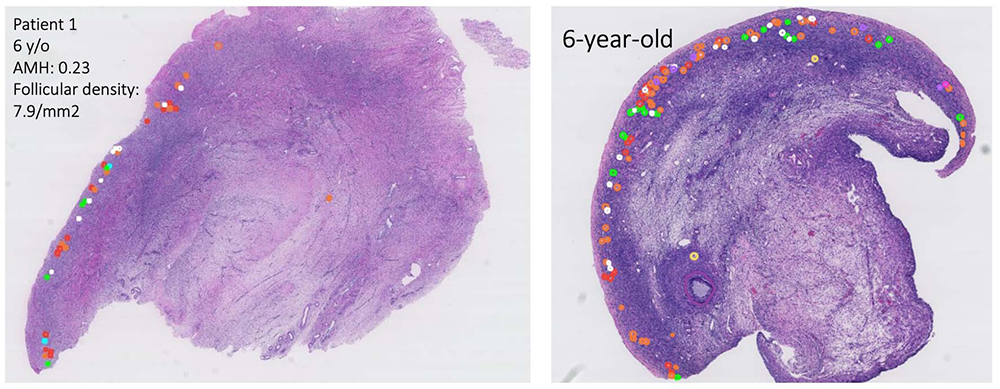

Dr. Gomez-Lobo was recruited to NICHD in 2019, just before the COVID-19 pandemic began. She and her team stayed busy during the next couple of years laying important groundwork, such as writing clinical research protocols and securing Institutional Review Board approvals. They also established an ovarian tissue image databank, which serves as a resource of microscopic ovarian anatomy, and a bank of tissue samples for research.

Credit: NICHD/Oncofertility Ovarian Tissue Slide Image Databank

Credit: Harbor’s family

Her group now leads three research protocols rooted in her experiences as a practicing physician, including one evaluating ovarian tissue freezing as a potential option to preserve fertility among young girls with rare conditions that compromise their ovarian function. The researchers also are examining the tissue to determine the causes of ovarian problems in these girls.

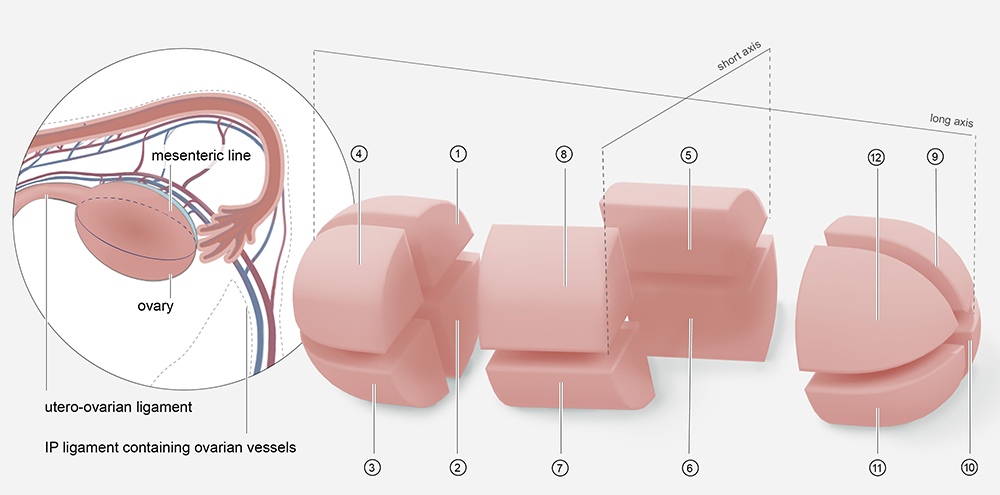

Ultimately, Dr. Gomez-Lobo’s team aims to generate a detailed description of the healthy human ovary, from the organ’s overall anatomy down to an analysis of individual cells. These findings will contribute to larger projects such as the Human Cell Atlas and NIH’s Human BioMolecular Atlas Program (HuBMAP) and allow for comparison with ovaries from individuals who experience accelerated loss of follicles—the small sacs in the ovaries in which eggs grow and mature.

“Our work on human ovarian tissue in both special populations and healthy individuals will enhance understanding of typical and atypical ovarian function,” says Dr. Gomez-Lobo. “Our findings may inform the development of treatments to enhance future fertility in special populations, as well as our understanding of fertility in women.”

To accelerate work toward these goals, Dr. Gomez-Lobo’s team convened a group of experts to standardize ovarian nomenclature and better describe the regions, structures, and cell types within human ovaries. The group has developed an updated three-dimensional model of the ovary and detailed many of the organ’s microscopic anatomic features. They are also working to refine the classification of follicle types and expand it to include transitional stages that occur during the growth and maturation of eggs, as well as abnormal forms and structures. By standardizing ovarian tissue collection, making it easier to track changes in ovarian structure and function over time, and facilitating comparisons between individuals, their work will help advance reproductive health research and knowledge.

Credit: NICHD

Passing the Baton to the Next Generation

Mentoring is extremely important to Dr. Gomez-Lobo, providing another way to bring PAG forward as a clinical subspecialty and a research field. “It’s so important to get people to take the baton and go on to the next step. Many of my trainees have gone further in their careers than I have,” she proudly notes.

“She encouraged me to think big with my career,” says Allison Mayhew, M.D., a graduate of NIH’s PAG fellowship program who now serves as director of PAG at Children’s National. “She set me up with research and leadership opportunities that allowed me to grow and explore and put me on a trajectory of career growth.”

Credit: Veronica Gomez-Lobo, M.D.

Drs. Maher and Damle agree. “From the beginning, she has treated me like an equal. She actively has helped advance my career and develop my niche in fertility preservation in children and adolescents,” says Dr. Maher, adding that Dr. Gomez-Lobo gave her speaking opportunities at scientific meetings within her areas of interest. Dr. Damle recalls Dr. Gomez-Lobo’s helping her prepare her first case report and submitting it to the annual NASPAG meeting.

“You can tell that she genuinely wants the best for you,” Dr. Mayhew adds. “She has a keen ability to identify strengths and help you hone your skills and career goals to meet those strengths. She is your cheerleader.”

Although each trainee’s needs are different, Dr. Gomez-Lobo feels commitment is a key predictor of career success. “In the end, success has to do with really wanting to do something—whether it’s research or clinical care—and asking for help and trying to grow,” she says.

A willingness to ask for help aided Dr. Gomez-Lobo during her own career transitions. Some of the feelings of insecurity she had when transitioning to PAG resurfaced when she first came to NIH as a clinician-educator with a modest research portfolio surrounded by Ph.D. colleagues with established laboratories. “I focused on what I knew and what I was good at, and I asked for help with things I didn’t know,” she says.

“Dr. Gomez-Lobo really values collaboration as a way to improve science,” says Dr. Maher. “She understands the importance of not being siloed and not trying to reinvent the wheel when you don’t have to.”

In addition to staying curious and learning from others, Dr. Gomez-Lobo advises early-career scientists to select their mentors carefully. A mentor should be accessible and willing to brainstorm with you, she notes, but they do not necessarily need to be in the same field. When she was becoming more involved in clinical research, some of the best advice she received came from a nephrologist (kidney specialist).

Dr. Gomez-Lobo also has a lot of experience with balancing priorities—as a mother of three, a wife, and a full-time physician-scientist. She remembers saying “yes” to nearly every request that she received early on in her career. “Each individual thing was small, but all together, it became very stressful. So now when I feel stressed out, I prune,” she says.

She encourages her trainees to periodically evaluate their professional and personal lives to identify stressors and other things that can be removed. This removal may mean turning down offers to serve on scientific committees, or it could mean hiring a service to assist with house cleaning.

“Dr. Gomez-Lobo gives me great advice on how to balance being a female physician with having a family,” says Dr. Maher, the mother of two young children. “She has helped me to feel less overwhelmed and to recognize that there are only so many hours in a day.”

Credit: Veronica Gomez-Lobo, M.D.

Looking to the Future

For Dr. Gomez-Lobo, looking forward means moving forward. She plans to spend the next decade making continued progress in defining the features of healthy human ovaries and elucidating factors underlying follicle loss in special populations. She hopes to advance knowledge about the effects of certain chemotherapies on the ovary and the potential benefits of ovarian tissue freezing for future fertility. She also looks forward to watching the next generation of clinicians and scientists blossom, including her two daughters, one a medical student and the other a resident.

Reflecting on her experiences, Dr. Gomez-Lobo notes that her path illustrates how multiple career transitions can happen. “People shouldn’t feel pegged into one area,” she advises. “New paths will open for you during your career. Don’t neglect them because of self-doubt or because you have a preconceived notion of the direction your career should follow.”

BACK TO TOP

BACK TO TOP