Credit: Ernesto del Aguilar, NHGRI

NICHD Director, Diana Bianchi, M.D., is not afraid to push boundaries. She’s an explorer. During medical school, she gladly tackled a research project that others deemed impossible and made it possible. Later in her career, she was undeterred by silos between medical disciplines and created one of the first research centers in the nation to team obstetric and pediatric specialists in caring for women and infants. In her newest position as NICHD Director, Dr. Bianchi saw the need for the institute to take a fresh look at its portfolio and chart potential research directions and activities. The resulting NICHD Strategic Plan outlines the institute’s ambitious research goals for the next five years.

“I don’t see myself as a pioneer like Kary Mullis, who invented PCR [the polymerase chain reaction]. But I think one of my contributions is connecting people, connecting disciplines, and connecting ideas,” she said.

Her ability to make these connections has helped guide her career and her life.

Growing up in New York City

Dr. Bianchi, a first-generation American, was raised along with her younger brother in Yorkville, on the Upper East Side of Manhattan. Her father was from San Colombano, Italy, and worked in the hospitality industry as a country club manager after earning his Ph.D. in economics. Her mother, from Berlin, Germany, was an actress and professor of speech and theater at Montclair State University in New Jersey. They met in Johannesburg, South Africa, and eventually settled in New York.

Credit: Diana Bianchi, M.D.

As a child, Dr. Bianchi was keenly interested in biology and nature, watching her cat deliver kittens and observing animals in the park. “Although my intellectual curiosity definitely came from my father’s side, I’m the ‘mutation’ in the family,” she said about her unique fascination with science. Despite not sharing her interests, no one in her family discouraged her pursuits.

Her neighborhood also provided certain advantages. “New York City is a great living laboratory. Part of my interest in medicine came from taking public transportation to school, either riding on the bus or subway. I would see people with congenital anomalies and wonder why they had that, what was wrong, what could be done, and could they feel better,” she remarked.

Credit: Diana Bianchi, M.D.

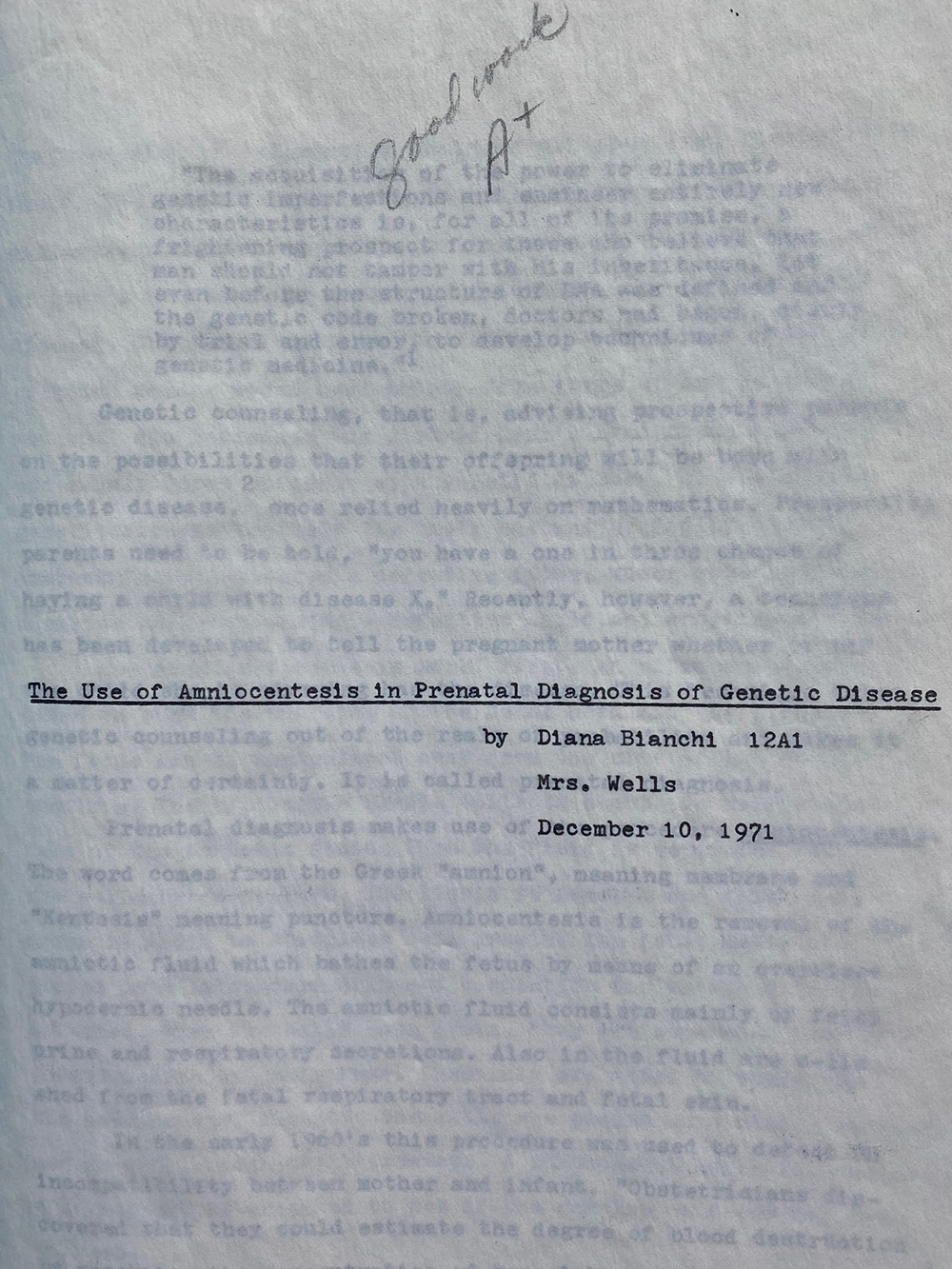

For middle and high school, Dr. Bianchi attended Hunter College High School, then all female. She had a very dynamic teacher, Mrs. Anita Wells, who taught 9th grade biology and 12th grade Advanced Placement biology. “I distinctly recall Mrs. Wells discussing a prenatal testing study, which I later found out was funded by NICHD,” she explained. The discussion piqued Dr. Bianchi’s interests and led her to work at a cytogenetics laboratory at Roosevelt Hospital. This experience enabled her to write her senior thesis and, importantly, it exposed her to two female pediatricians. It was here that Dr. Bianchi first envisioned a future that connected her intellectual pursuits of being a physician and a researcher.

Training Across Disciplines

Credit: Diana Bianchi, M.D.

This vision influenced many of her decisions. When it came time for college, Dr. Bianchi picked the University of Pennsylvania because it had a human genetics department, which was highly unusual at the time, and the medical school was on the main campus. During all four years as an undergraduate, she worked with various staff in the human genetics department and spent her summers in the Cytogenetics Lab at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia.

Her female role models at the time—Elaine Zackai, M.D., a pediatric medical geneticist, and Beverly Emanuel, Ph.D., a postdoctoral researcher—further reinforced her vision. One had clinical experience, the other had scientific experience, and both had young children. If they could balance a medical career and family, she could too.

As she applied to medical school, Dr. Bianchi wanted to fulfill a longtime dream of living in California. “When I was accepted to Stanford, it was around my birthday, and I told my parents that all I wanted for my birthday was a plane ticket to California,” she recalled. During her visit, she was impressed by how happy the Stanford University medical students were, the program’s emphasis on research, the beautiful campus, and the warm California weather. She graduated from Penn magna cum laude in 1976 and headed west. “There was a spirit of innovation, great education, and research. My time at Stanford set me on the path to my career as a clinician-scientist.”

Credit: Diana Bianchi, M.D.

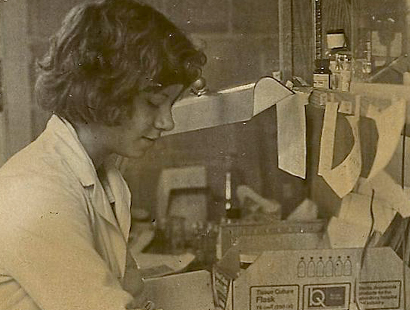

As a medical student, Dr. Bianchi worked with Howard Cann, M.D., Leonard Herzenberg, Ph.D., and his wife Leonore Herzenberg, D.Sc. Dr. Len Herzenberg had recently invented the fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS), which enabled researchers to count and sort different types of cells from blood samples. The Herzenbergs were interested in Down syndrome, which is caused by an extra copy of chromosome 21. One of their children, Michael, had the condition. At the time, there was no prenatal screening available. The Herzenbergs asked Dr. Bianchi to use FACS to look for fetal cells in blood samples from pregnant women. If they could collect these cells, they could then test them for genetic disorders.

“There’s something about being young and naïve and feeling like you can do anything. I didn’t actually realize how difficult the project would be,” said Dr. Bianchi. She remembers driving around the San Francisco Bay area, visiting pregnant women in their homes and drawing blood from the women and their partners to identify fetal cells.

In 1979, she published a paper confirming that it was indeed possible to detect fetal cells in maternal blood. That same year, Dr. Bianchi spent a rotation at NIH Clinical Center, giving her a first glimpse at its role in funding biomedical research across the nation, and as the world’s largest hospital dedicated to research.

She and other researchers built on these early findings with additional advances, such as isolating DNA from these fetal cells. In 2008, scientists eventually developed a precise, non-invasive prenatal screening test (commonly called NIPT) for Down syndrome using placental DNA fragments that float in the blood of pregnant women. Such screening was initially offered for pregnancies at high-risk for fetal chromosome abnormalities, but in 2014, Dr. Bianchi showed that screening is just as useful for women with general or low-risk pregnancies.

Toward the end of medical school, Dr. Bianchi found it difficult to choose between specializing in obstetrics/gynecology (ob/gyn) or pediatrics. She eventually chose the latter. The small children’s hospital at Stanford and low birth rates in San Francisco meant that her California time was over. “I had the California experience. I missed my family. So, I knew I was coming back to the East Coast,” she said. She was accepted into an internship and residency in the pediatrics department at Boston Children’s Hospital, part of Harvard Medical School.

After her residency, Dr. Bianchi opted for fellowship training in neonatology-perinatology, a subspecialty that connects ob/gyn with pediatrics by focusing on premature newborns who spend time in intensive care.

Credit: Diana Bianchi, M.D.

She was also interested in genetics, but medical genetics was not yet a recognized medical specialty. Because of her background in cytogenetics research, she was accepted into the laboratory of Samuel Latt, M.D., Ph.D., who was chief of the Genetics Division at Boston Children’s Hospital.

“I was among the first researchers to receive a Physician-Scientist Award from NICHD,” said Dr. Bianchi. “At the time, they called it the K11, and I got it on my first attempt.” Ultimately, Dr. Bianchi spent 13 years at Harvard as a trainee, attending physician, and assistant professor. She also became board-certified in pediatrics, neonatal and perinatal medicine, and medical genetics.

Credit: Diana Bianchi, M.D.

Lessons in Resilience

“[As an actress] my mother went to a lot of casting calls, and she would have many rejections for every job she got. When I was younger, I told myself that I would never do something like that,” recalled Dr. Bianchi with a laugh. “And then I went into academic medicine and had to deal with my papers getting rejected, or my grants not getting funded.” She added, “Although I didn’t realize it at the time, seeing my mother persist in her quest to act, I learned skills related to resilience.”

Those skills would serve her well in both her professional and personal life.

“I was widowed at the age of 28,” she said. “My first husband, Tim, had a family history of melanoma, but we didn’t know then what we know now. Shortly after we got engaged, he was diagnosed with melanoma. The dermatologists thought they caught it early, but two years later, it metastasized, and he died.” She added, “It’s not what you expect to experience at that age. He passed away just as I was finishing up my residency.”

Then, five years later, her mentor Dr. Latt died unexpectedly. “Career-wise, everyone acted like nothing had happened. Colleagues didn’t know what to say. I was transferred to a new mentor, but he wasn’t as interested in my project. The experience fostered independence.”

Today, Dr. Bianchi encourages people to seek help with their grief. She attended a support group for young widows and widowers, where she eventually met her second husband, John. When they got married, they asked their guests to make donations to the support group in lieu of wedding gifts. They have two sons, Joshua and Elliott. Dr. Bianchi credits John with helping her balance career and family. “You can’t do what I do without a very supportive spouse. My husband is a nurturer. And the fact that he is a nurturer has allowed me to do what I do,” she said.

As Dr. Bianchi continued in her career, she had a vision of linking prenatal and pediatric care, but she ran into roadblocks. “I tried really hard to connect the two, but a senior faculty member from the ob/gyn department at Brigham and Women’s Hospital told me that they never had someone from Boston Children’s Hospital on their faculty. At the time, they didn’t do multidisciplinary appointments.”

Synthesizing Opportunities

In 1993, Dr. Bianchi moved to Tufts University School of Medicine, where she was recruited as a neonatologist and leader in reproductive genetics. To her delight, Tufts had moved their maternity service to the main Medical Center campus. “There were suddenly new opportunities, and they were looking for someone to synthesize these opportunities.” The atmosphere at Tufts was very multidisciplinary and collegial. The departments of ob/gyn, pediatrics, neonatology, and genetics all worked closely together, which not only facilitated coordinated care, but led to an award-winning textbook, Fetology: Diagnosis and Management of the Fetal Patient, which has been translated into Mandarin, Japanese, and Spanish.

During her time at Tufts, Dr. Bianchi rose through academic and leadership ranks and among many roles, was chief of the Division of Genetics in the department of pediatrics and the Natalie V. Zucker Professor of Pediatrics, Obstetrics and Gynecology, an endowed chair. In 2008, Dr. Bianchi participated in the Hedwig van Ameringen Executive Leadership in Academic Medicine (ELAM) Program, where she was required to develop an action project. That’s when she sketched out the ideas for the Mother Infant Research Institute (MIRI) .

“When I came back from ELAM, I was emboldened. There were three research institutes at Tufts, but none were dedicated to women’s health or pediatrics,” she said. She made a business case for why the medical center needed an institute focused on health problems that could be addressed by a team with expertise in both obstetrics and pediatrics.

In 2010, MIRI was established at Tufts, and Dr. Bianchi was named the Founding Executive Director.

Following the Data

Throughout her 23 years at Tufts, Dr. Bianchi continued to make groundbreaking scientific discoveries. “One of the things I always tell my trainees—don’t get so fixed on a hypothesis that if the results do not give you what you expect, you’re disappointed. You’ll blind yourself to what you’re actually seeing. You have to follow where the data lead you.”

For example, when NIPT results were confusing, some providers declared the test inaccurate. “If you looked at the data and clinical follow-up, you realized the testing was accurate. We just didn’t understand what the test results were telling us. As one example, it turned out that maternal tumors were shedding DNA into the blood of the pregnant woman and giving a false-positive test result.” The findings that NIPT could detect cancer in pregnant woman opened up discussions on how physicians should handle unexpected and sometimes limited results in the management of patient care.

Dr. Bianchi’s research also led to the discovery of “fetal microchimerism,” which occurs as a result of pregnancy. Her work showed that fetal cells persist in the mother’s body, even as long as 27 years postpartum. They can retain stem cell-like properties and possibly help repair maternal organs. These fetal cells may also play a long-term role in the mother’s health and possibly explain why pregnancy lowers a woman’s risk for certain conditions, such as breast cancer.

Dr. Bianchi has also continued to study Down syndrome, exploring whether treatments offered during pregnancy might improve long-term health outcomes. In 2009, her team showed that reducing oxidative stress may be a potential drug target. “Ten years ago, I would have said, ‘This is crazy.’ But we have preliminary evidence to suggest that we can improve brain development, learning, and memory in mouse models of Down syndrome. By facilitating prenatal treatment, one may get an increase in independent life skills in people.”

Credit: Diana Bianchi, M.D.

Dr. Bianchi remains passionate about her work, but she still connects with other interests. “If I had another career, I would have been a docent in an art museum. I love the stories related to paintings.” She’s also a “Vermeer completist,” meaning that she aims to see all Vermeer paintings in person. “Art teaches you to be an excellent observer. I always challenge myself when I go to see these paintings, to see something new in them. You can do the same with your data. You think you understand it, but you can look at it in many different ways and challenge yourself to find a new interpretation.”

Dr. Bianchi also sees parallels between grant writing and painting. “I always enjoyed writing grants. It’s akin to creating a giant painting, and you’re just putting your vision out there. People are going to react to it. They’ll either love it or hate it or consider it so-so. In the process of that creation, you learn a lot, and it forces you to think about the next step,” she said.

Paying It Forward

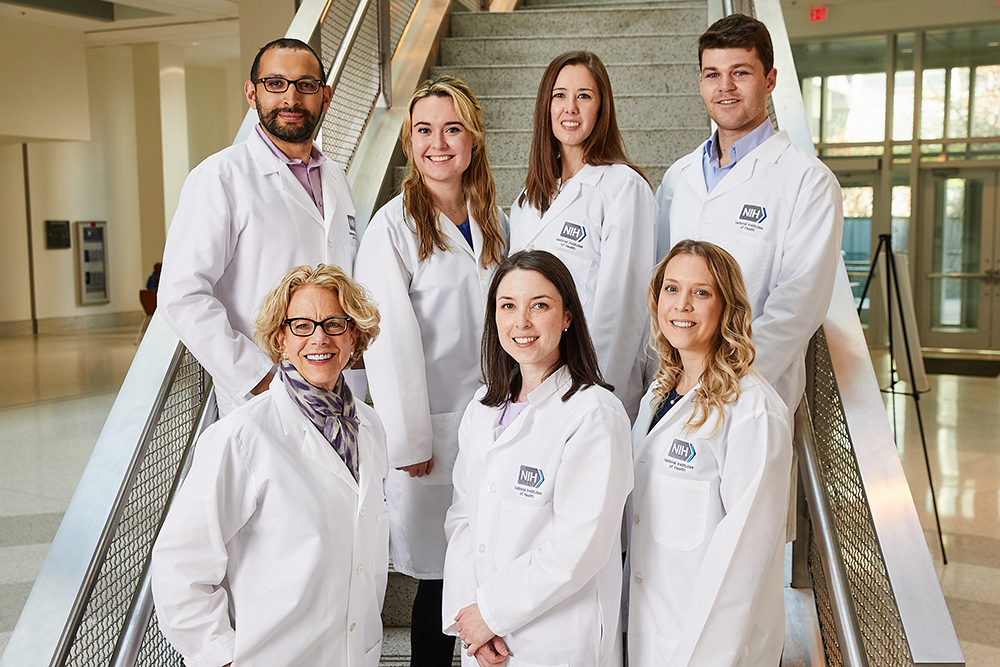

Her passion for research is enhanced by her commitment to mentoring the next generation and being a role model for younger female scientists.

“Dr. Bianchi will always be the person who encouraged me, who taught me how to do good science, and who taught me to think outside the box,” said Jill L. Maron, M.D., Ph.D., who trained under Dr. Bianchi for many years and succeeded her as Executive Director of MIRI. “Here was a true role model who never gave up, who kept going, who would allow herself one day to feel sad and say, ‘Well, now we best get back to work.’ I still try as best as I can to take that approach in my own life and as a mentor myself.”

“Dr. Bianchi has been one of my most formative scientific and career mentors,” added Andrea Edlow, M.D., M.Sc., a former trainee who is now an assistant professor of obstetrics, gynecology and reproductive biology at Harvard Medical School. “Her intellectual curiosity, scientific innovation and rigor, commitment to mentoring women in science and physician-scientists, and impactful, practice-changing discoveries, are all defining qualities of her and her work that I will spend my career seeking to emulate. I will always be grateful to her for her steadfast support during times of great personal and professional transition, whether it was the birth of my first child or starting my own laboratory. We joke that she’s my ‘science mom,’ but it’s really true.”

Credit: NIH

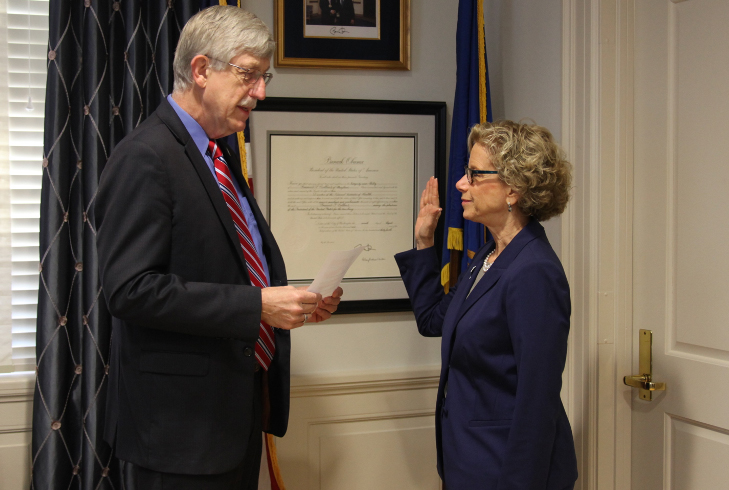

In 2016, Dr. Bianchi chose to push her own boundaries yet again when she left Tufts following her appointment as director of NICHD, a position that some refer to as the “nation’s pediatrician.”

“My favorite thing about working at NIH is that we are the ‘House of Hope’, and our mission is very clear. We’re not running a business, we’re here to help, to advance science in the name of making people’s lives better. It’s the purest mission,” she said.

She also continues to conduct research, leading a lab in the Medical Genetics Branch at the National Human Genome Research Institute, where she and her team are studying secondary genomic findings that are detected by routine prenatal screening, understanding whether cell-free DNA in amniotic fluid can offer insights on how to treat genetic and/or health conditions during the prenatal stage, and developing prenatal therapies for Down syndrome.

During her short time at NICHD, she has received multiple honors, including the Colonel Harland D. Sanders Lifetime Achievement Award in Genetics from the March of Dimes in 2017 and the J.E. Wallace Sterling Lifetime Achievement Award in Medicine from Stanford, also in 2017. She received an honorary doctorate from the University of Amsterdam

in 2020. She has published over 300 peer-reviewed articles.

In both her professional and personal life, Dr. Bianchi continues to stress the importance of connecting with new ideas and continuing to challenge yourself, no matter your position or age. “Multidisciplinary science is critical. It’s not good to stay in one box. For example, I’m giving a talk on artificial intelligence, and I don’t know much about it. To prepare, I’m reading and talking to experts.”

BACK TO TOP

BACK TO TOP