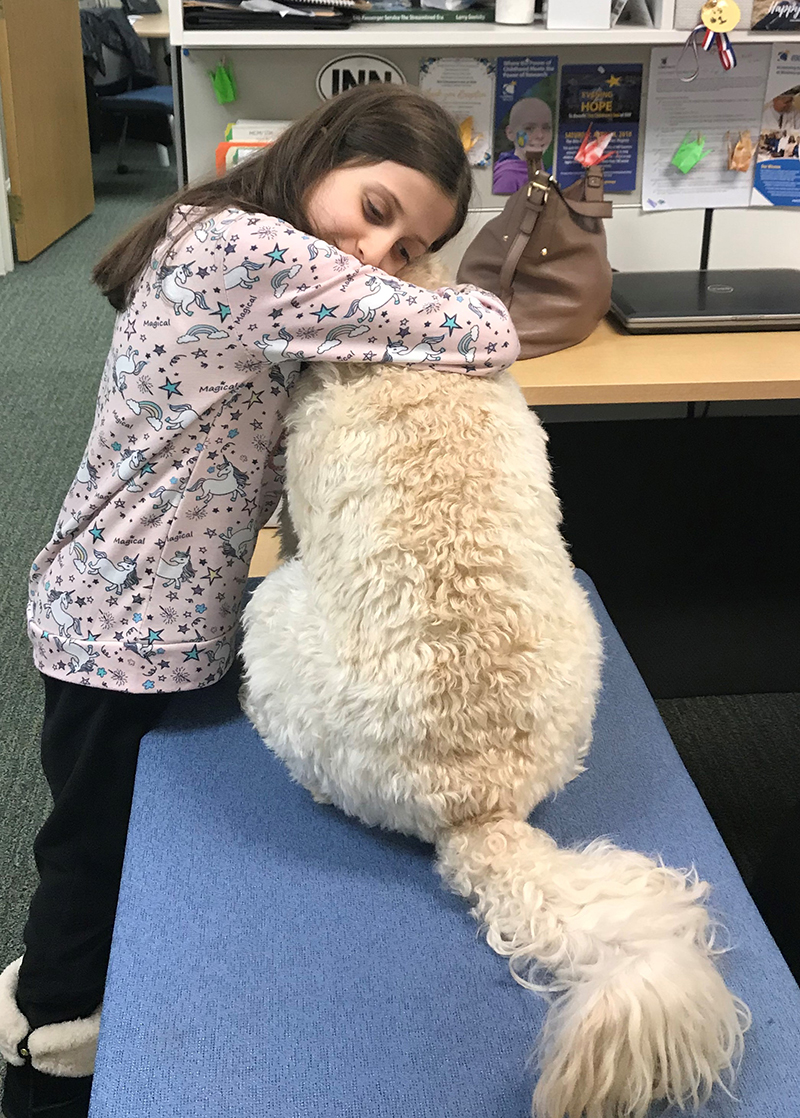

Credit: Lina El Zein

Lina El Zein has been bringing her three young children to NIH from Dubai to participate in a research study since 2018. The 14-hour flight is long, and the treatments challenging, but a welcome from a special friend at The Children’s Inn at NIH has made the visits far more enjoyable. The Children's Inn is a nonprofit Place Like Home for seriously ill children who come from around the world and across the country to participate in groundbreaking medical treatments as part of research studies at NIH.

“Zilly works her magic,” the mom said.

Zilly, the Inn’s curly haired therapy dog, helped motivate Lina’s daughter Luana, 9, to get back on her feet after surgery last year. Doctors encouraged Luana to start walking to boost her recovery, but the pain was intense. That’s when a visit from Zilly became the best medicine. Luana couldn’t resist walking to see Zilly, tail wagging and always glad to see her. Each visit became a little easier, and the walking a little better. Her youngest son, Jude, had an extreme anxiety of dogs before coming to the NIH. Now, during the long flight, he counts down to Zilly time.

“Anecdotes like these are plentiful, but research has been sparse,” said James A. Griffin, Ph.D., Acting Chief of the Child Development and Behavior Branch in NICHD’s Division of Extramural Research.

Sparse until 10 years ago, when NICHD and the WALTHAM® PetCare Science Institute

“HAI had never been systematically studied before,” Griffin said. “We had a lot of stories, but no real evidence. We didn’t know how pets and animals impacted child development.”

Funding opportunities from the partnership launched multiple studies of pets with participants ranging in age from infants to adolescents to young adults. The studies also aimed to measure the impact of therapy animals, so they included people with physical and intellectual disabilities and those in need of medical rehabilitation. To understand the full range of effects, the research incorporated a variety of animals—dogs, horses, cats, guinea pigs, and fish.

Most importantly, the research utilized robust and quantifiable measurements and tools, such as testing blood cortisol levels to assess stress and monitoring heartbeat and breathing rate to evaluate individual differences during interactions with animals. Griffith noted that these methods and measurements were critical to building the field of HAI and proving the effects are more than just anecdotes.

Some highlights from the partnership’s studies include the following:

- A 2015 study examined the effects of caring for fish on blood sugar control in adolescents with type 1 diabetes. The researchers found that, compared to teens who did not take care of a fish, the fish-keeping teens were more disciplined about checking their own blood glucose levels. Kids ages 10 to 13 years in the study showed the greatest increase in self-monitoring following the fish care intervention.

- Another study found that children with autism spectrum disorder were calmer while playing with guinea pigs. When the children with autism spent 10 minutes in a supervised group playtime with guinea pigs, their anxiety levels dropped. They also showed improved social functioning and were more engaged with their peers who did not play with the animals—an important benefit for children with autism.

- Another study from this partnership suggests that dogs may help kids cope with attention-deficit-hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Kids with ADHD who read to dogs and taught dogs specific commands performed better in measures of social skills, prosocial behaviors (such as sharing, cooperation, and volunteering), and behavioral problems than their peers who did the same activities with dog puppets.

The partnership’s research will continue to explore and evaluate interactions with animals and the impact of these interactions on child development. The researchers also recommend incorporating video data sharing into future projects, based on the success of the Databrary, a platform through which researchers archive and share video data. This data library, partially funded by NICHD and the National Science Foundation, improves researchers’ ability to replicate study measures and to accelerate scientific discoveries.

Lina notes that there are plenty of video clips of her children playing with Zilly at The Children’s Inn, and she’d be happy to share them. “Having Zilly around helps them just be kids,” she said.

BACK TO TOP

BACK TO TOP