Credit: Tracey Rouault, M.D.

Tracey Rouault, M.D., has had many notable achievements during her nearly four-decade career at NIH. She notes that her scientific acumen and leadership skills were honed by a range of unique experiences.

“I got into Yale [College] the first year that they enrolled women for all four years of undergrad. There were 250 women among 1,000 men,” Dr. Rouault explained. “My high school was not a setting where people aspired to ‘rule the world.’ Yale was very different, and it got me thinking outside the box.”

Today, Dr. Rouault is a Distinguished NIH Investigator (an honorific reserved for NIH’s most preeminent senior investigators), head of her own laboratory—the Section on Human Iron Metabolism—and a veteran, having served 26 years as a commissioned officer in the U.S. Public Health Service. Her latest series of research papers identify promising therapies for COVID-19 and other viral infections, including ones with no approved treatment.

“[Dr. Rouault] has made multiple unexpected and surprising findings during her career at NICHD,” shared colleague Rodney Levine, M.D., Ph.D., a senior investigator and chief of the Laboratory of Biochemistry at NIH’s National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. “Anyone can stumble upon one such discovery, but to do it repeatedly is no accident.”

Early Years in the Northeast

Dr. Rouault spent most of her youth in different towns of upstate New York, where her father worked as an engineer for General Electric and her mother focused on raising a family. “My mother wanted to be a writer. She won a writing contest that was sponsored by Atlantic magazine, which gave her a scholarship to attend the prestigious Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference

Credit: Tracey Rouault, M.D.

From an early age, Dr. Rouault played the piano and considered pursuing a career as a concert pianist. But as she reached different milestones during childhood and adolescence, she decided against it. In 1969, she attended Yale and majored in biology. There, she found like-minded students who were serious about studying, had high ambitions, and were driven. “Many of the women in my undergraduate class went on to graduate school, especially medical school,” she said.

A mentor, Elga Wasserman, Ph.D.

Training at Duke University

After graduating cum laude from Yale in 1973, Dr. Rouault knew that she wanted to gain experiences outside of the Northeast, and Duke Medical School had an excellent reputation. “I chose Duke because its mission is to train physician-scientists. They condensed two years of medical courses into one year, which made the work very difficult. But it freed up that third year to pursue research,” said Dr. Rouault.

At Duke, Dr. Rouault conducted research on a life-threatening blood disease called paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH) and published her very first research paper, which explained how the immune system destroyed red blood cells in patients with PNH. “Publishing a paper and reporting a discovery probably does something to your dopamine receptor and reward pathway,” she said. “It put a hook in me, and my appetite was whetted for research.”

Dr. Rouault chose internal medicine and rheumatology as her specialties. “There were very few women in internal medicine, and people were wary of me at first,” she explained. But she did not let that icy reception dissuade her from pursuing her interests and goals. “Those two specialties are particularly challenging. You have to figure out what’s going on. Diagnostic challenges are like puzzles to solve, and I excel at puzzles.”

Dr. Rouault also met her husband, W. Marston Linehan, M.D., while at Duke. For her psychiatry rotation, she spent an overnight shift at the hospital where he was a surgery resident, required to arrive early in the morning. “It was not the most romantic setting, but we met over breakfast in the hospital cafeteria,” she shared. They married and learned to balance career and family together throughout the years.

In 1977, Dr. Rouault graduated from medical school and then completed both of her residencies at Duke. She became board-certified in internal medicine in 1982 and board-certified in rheumatology in 1984.

Carving a Path at NIH

As the young couple wrapped up their medical training in Durham, Dr. Linehan found a job as a urologic oncologist at NIH’s National Cancer Institute. The family moved to Bethesda, Maryland, where they experienced “sticker shock” as they adjusted to a new standard of living in the Washington, D.C., area.

“I just had the first of my two daughters and did not feel hireable at that point. But we needed the second income, so I moonlighted,” explained Dr. Rouault. She spent evenings as director of house physicians at Sibley Hospital, where she led a team that handled 24-hour emergencies. “Working at Sibley gave me management experience, especially because we dealt with tense situations, like heart attacks and sudden death syndromes,” she said. Over the years, she continued to gain valuable administrative and management skills.

Eventually, a friend told her about a fellowship opportunity—with a four-month rotation and two years of research—in the Human Genetics Branch at NICHD. “It was a low-paying but good opportunity, and I hoped it would position me for better jobs in the future,” said Dr. Rouault. Her interest in research never waned, though she knew it would take time and commitment to succeed.

“Biomedical research is not for everyone. You need to be driven,” Dr. Rouault shared. “It was also a big challenge because I just had my second daughter, and I had to be like the others at work. I could not work just half the time, and there were very few daycare centers.” She was the only mother in her program.

“Each step of the way, we had to figure out how to manage. Nothing was straightforward, but my husband was very encouraging,” said Dr. Rouault. “Flexibility is important. There are many potential career paths, and your current project does not have to work out. You can change your goals and refocus many times before you find a successful and rewarding career.”

John O’Shea, M.D., then a fellow trainee and now Scientific Director of Intramural Research at the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases, recalled that NIH had tennis courts on campus at that time. “I was terrified playing tennis as Tracey’s opponent in the face of her skill, energy, and focus. I was very much a novice molecular biologist and was impressed by how she put these same attributes into her science.”

After her fellowship ended in 1989, Dr. Rouault was hired as a senior researcher. Only two years later, in 1991, NICHD’s intramural scientific director, Arthur S. Levine, M.D., promoted her via a commission in the U.S. Public Health Service—a recognition that was only offered to outstanding investigators. The commission essentially paved the way for her to start her own independent laboratory (NIH did not have a formal tenure system at the time). She has led this same laboratory—the Section on Human Iron Metabolism—for nearly 33 years.

Credit: Tracey Rouault, M.D.

Making New Discoveries

“Right around the 1980s, the concept of the gene promoter (where transcription begins) was developed. People thought all types of regulation would take place at the promoter—at the transcriptional level,” explained Dr. Rouault. “We focused on iron metabolism because it’s such a key element, a cell has to get it right. We thought it would be a good system to identify other ‘tricks’ for cellular regulation and for maintaining homeostasis.”

Soon, Dr. Rouault and her colleagues identified a regulatory system that was not dependent on transcription. Her work found that, instead, a protein (the product of an RNA transcript) formed a second level of regulation. She identified and cloned two iron-responsive proteins, called iron regulatory protein 1 (IRP1) and 2 (IRP2), that could “sense” iron levels in a cell and regulate translation of genes involved in iron metabolism. Her discovery of these regulators changed how scientists viewed regulation of cellular iron metabolism.

When a cell has sufficient iron, IRP1 functions as an aconitase enzyme, catalyzing elements into products needed for making ATP and heme in the cell’s cytoplasm, where it requires an iron-sulfur cofactor to directly bind its substrate. When a cell lacks iron, fewer iron-sulfur cofactors are available, causing a conformational change in IRP1 that enables it to bind to iron-responsive elements—RNA loops involved in transcription. The conversion and binding suppress the translation of many proteins important in iron metabolism but enhances mRNA levels of other proteins. The overall effect increases iron uptake, because cells need more iron to complete cellular processes, and reduces iron storage.

“The fact that IRP1 can dramatically change from an enzyme to a translational regulatory protein illustrates the importance of learning the details that govern protein expression at the molecular level,” said Dr. Rouault. “The elegance of this regulatory system would not have been uncovered in experiments that sought to discover everything, such as expression arrays and proteomics, which often dominate the research world today. We showed that a regulatory protein can sense what it’s regulating and change its behavior accordingly. It’s still one of the best examples of an RNA-protein interaction that results in regulation.”

In the 2000s, Dr. Rouault’s laboratory also discovered that mice without IRP2 developed a progressive and ultimately fatal neurodegenerative condition similar to Parkinson’s disease and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (NICHD Scientists Discover Mouse Disorder, Search for Human Analog [PDF 1.2 MB]). Importantly, they found that an antioxidant drug called Tempol could restore iron metabolism in their mouse model and that Tempol prevented symptoms from getting worse if given early enough. Dr. Rouault and her team shared these findings with healthcare providers to identify patients with IRP2 mutations and apply the treatment.

“Her work characterizing the mouse model missing IRP2 stands out as a pivotal achievement,” said Nunziata Maio, Ph.D., a staff scientist in Dr. Rouault’s laboratory. “Remarkably, this model anticipated the first human patient with biallelic loss-of-function in IRP2 by nearly two decades, and the mouse model effectively mirrored what was seen in people. It was only through a very thorough and careful analysis that Dr. Rouault and her team were able to uncover these findings that fundamentally changed not only our understanding of iron metabolism, but also the implications of disruptions within this pathway for human health and disease.”

Encouraging Independent Thinking

Throughout her NICHD career, Dr. Rouault has also become known for her leadership and mentoring.

“Dr. Rouault constantly encourages us to formulate our own questions and pursue them rigorously. Her genuine respect for the ideas we contribute and the trust she places in each of us serve as powerful sources of motivation,” said Dr. Maio. “There is really nothing that compares to the sense of accomplishment that derives from being able to independently address your own scientific questions in a field that can be very competitive and often not very mindful of trainees’ perspectives.”

Esther Meyron-Holtz, Ph.D.

“[Dr. Rouault] also taught me to stop often and look at the data. I used to prefer to plan my next experiment before thinking deeply about the results of the former,” she continued. Advice from her former mentor also assisted Dr. Meyron-Holtz when she was nervous before giving a talk. “She would say, ‘You are the one who chooses how nervous you want to be.’”

Trainee and doctoral candidate Audrey Heffner joined Dr. Rouault’s lab during the pandemic. “Dr. Rouault's mentorship and leadership provided a comforting presence during those challenging times. Amid uncertainty, witnessing her dedication to open dialogue and continuous learning was a guiding light. It motivated me to seek diverse perspectives and remain adaptable in the face of evolving scientific landscapes,” shared Ms. Heffner.

“Her openness to new challenges, combined with her ability to find humor in challenging situations, showed me that resilience and a positive outlook can be powerful tools in research and life alike,” she added. “Dr. Rouault's leadership has not only enriched my understanding of science, but also provided valuable life lessons that I continue to apply in my journey as a young researcher.”

On the Trail of SARS-CoV-2

In recent years, Dr. Rouault’s lab discovered that some viral proteins also use iron-sulfur cofactors, opening a new frontier in understanding viral infections. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, the lab had identified a “motif” (amino acid sequence) that would signal whether a protein might require an iron-sulfur cluster for its function.

“During the early days of the pandemic, they allowed one person in each lab to come back to work on COVID-related research,” remembered Dr. Rouault. “So, I went in and checked whether any SARS-CoV-2 proteins had the motif and found that many of them were candidate iron-sulfur proteins.”

The first viral protein they studied was replicase, which is essential for the virus to replicate and cause infections. They found that replicase needed two iron-sulfur clusters. Since then, they have identified a similar requirement for helicase, which helps unwind viral RNA strands. These features help explain why Tempol appears effective as a potential COVID-19 therapy.

“It’s very interesting because virology is a big field and, before this, only a couple of viral proteins were identified as needing an iron-sulfur cluster. This feature was regarded as an oddity. But now, we’ve shown that incorporating an iron-sulfur cofactor is actually central to the activity of multiple viral proteins,” said Dr. Rouault. “It’s an exciting new theme that gives us a whole new perspective on viruses.”

Dr. Rouault’s lab is evaluating other viral proteins, including those involved in monkeypox, to determine whether the cofactors play a role in infection or transmission. “Tempol is approved for use as a topical ointment, and pox lesions are very painful and very contagious. So, if we have another outbreak, someone could develop a clinical trial using Tempol as an experimental treatment for these lesions,” she said.

Looking Forward

Dr. Rouault has many goals for herself and her lab over the next decade. “I want to discover more human proteins that utilize iron-sulfur cofactors, which could alter many biochemical pathways. I also want to continue pursuing the role played by iron-sulfur cofactors in viral infections, which could lead to better therapeutics,” she said.

She also seeks to understand neurodegeneration in the mouse model lacking IRP2. She hopes these studies, already underway, may help explain why the axons of neurons degenerate. Insights gained from these studies may identify the molecular pathways that underlie other neurodegenerative diseases.

Dr. Rouault is also grateful for the scientific freedoms afforded by the NIH intramural program. “We are funded based on our track record, rather than having others decide whether something will or will not work,” she explained. “It encourages more risk-taking and allows us to pursue ideas, regardless of what goes in and out of scientific fashion.”

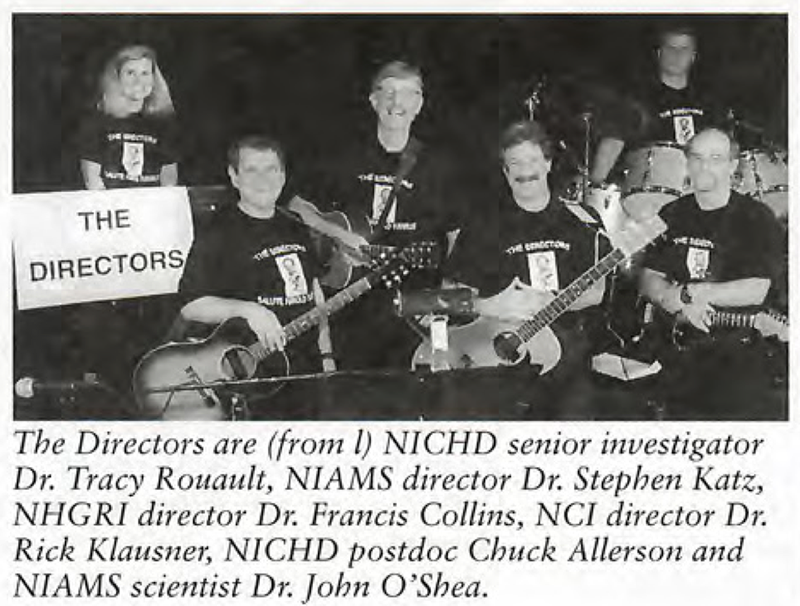

Outside of work, Dr. Rouault remains an accomplished musician and has been a member of several bands at NIH throughout the years. She and her husband also helped oversee the donation of the concert grand piano to the NIH Clinical Center in 2006. A video clip of Dr. Rouault

Credit: NIH Record

Credit: Tracey Rouault, M.D.

In 2012, Dr. Rouault and other NIH musicians performed at the Kennedy Center for the Celebration of Science fundraising event. Whoopi Goldberg served as emcee and gently cautioned the crowd not to expect much from a band composed of physicians. Dr. Rouault remembers that the band performed beyond the crowd’s expectations and that Ms. Goldberg congratulated her afterward for her keyboard skills. In the future, Dr. Rouault hopes to form a piano trio.

In taking stock of her accomplishments, Dr. Rouault said she is “proud of my husband and daughters, of my achievements at work, and the resilience I needed to carve out a career path when it often seemed impossible.” When she encountered difficult barriers, Dr. Rouault simply changed directions, and recommended that course of action to others. “Don’t box yourself in or wed yourself to only one career path, and get the degrees that you need to have flexibility.”

BACK TO TOP

BACK TO TOP