NIH study shows surgery reduces rate of disability, increases preterm birth risk

A surgical procedure to repair a common birth defect of the spine, if undertaken while a baby is still in the uterus, greatly reduces the need to divert, or shunt, fluid away from the brain, according to a study by the National Institutes of Health and four research institutions.

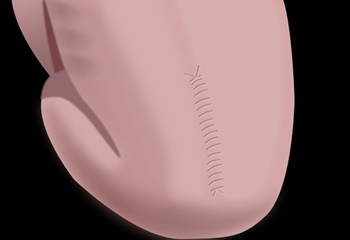

The surgical procedure consists of closing an opening at the back of the fetal spine. The fetal surgery is a departure from the traditional approach, which involves repairing the defect in the spinal column after an infant has been born.

The fetal surgical procedure also increases the chances that a child will be able to walk without crutches or other devices.

However, infants who underwent this prenatal surgery were more likely to be born preterm than were the infants who had the surgery after birth, when it is typically performed. As with all infants born early, preterm infants in the study were at increased risk for breathing difficulties. Mothers who underwent the surgery during their pregnancies were at risk for uterine dehiscence, a thinning or tearing at the incision in the uterus.

Myelomeningocele is the most serious form of spina bifida, a condition in which the spinal column fails to close around the spinal cord. With myelomeningocele, the spinal cord protrudes through an opening in the spine.

Originally planned to enroll 200 expectant mothers carrying a child with myelomeningocele, the Management of Myelomeningocele Study (MOMS) was stopped after the enrollment of 183 women, because of the benefits demonstrated in the children who underwent prenatal surgery.

The study appears in the New England Journal of Medicine and was conducted by researchers at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP), The UCSF Benioff Children’s Hospital at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF), Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville, the George Washington University Biostatistics Center in Washington, D.C., and the NIH’s Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD).

"In spite of an increased risk for preterm birth, children who underwent surgery while in the uterus did much better, on balance, than those who had surgery after birth," said Alan E. Guttmacher, M.D., director of NICHD, which funded the study. "However, caution is advised. Because the surgery is highly specialized, it is best undertaken in facilities with staff having experience in the procedure."

The study authors noted that myelomeningocele occurs in 3.4 of every 10,000 births, and 10 percent of affected infants die. Spina bifida is one of a class of birth defects known as neural tube defects, in which the brain or spine fails to develop normally in the early embryo. The condition often results in weakness or paralysis below the location of the defect on the spine. In addition to loss of bladder and bowel control, individuals with myelomeningocele often are unable to walk unassisted or may need a wheelchair. Also, the protrusion of the spinal cord creates a change in the flow of spinal fluid that may pull the brain stem into the base of the skull, which is known as hindbrain herniation. Children with myelomeningocele are subject to blockages that hinder or shut off the circulation of cerebrospinal fluid in the brain. The resultant fluid buildup can be life-threatening, and so a tube, or shunt, is inserted into the brain to drain the excess fluid into the abdominal cavity. These shunts are susceptible to blockage and infection, and may require many replacements during the patient’s lifetime.

Surgery for myelomeningocele has traditionally been undertaken after birth, explained co-author of the study Catherine Y. Spong, M.D., chief of NICHD’s pregnancy and perinatology branch. It consists of inserting the cord back into the spinal cavity and sealing the opening with sutures. Study authors N. Scott Adzick M.D. of CHOP and Diana L. Farmer, M.D. of UCSF performed the initial animal studies suggesting that surgery in the womb might prevent many of the complications of myelomeningocele.

Women volunteering for the current study were assigned at random to one of two groups. The first group underwent prenatal surgery to close the spinal defect in the fetus before their 26th week of pregnancy. The second group had the surgery performed on the child after birth.

The children were examined at 12 months of age and again at 30 months. The study results were evaluated for two separate primary outcomes. The first primary outcome took into account whether, by 12 months, a child had died, or required a shunt. The second primary outcome, at 30 months, was a composite from a test of mental development and an assessment of motor function. The mental development score was taken from the Bayley Scales of Infant Development II Mental Development Index. The motor assessment score was calculated as the difference between the child’s actual motor ability and the expected ability given the level of the defect on the spine.

The first primary outcome, death or the need for a shunt, was much less likely in those who had prenatal surgery, occurring in 67.9 percent of the infants in the prenatal surgery group and 97.5 percent of the traditional surgery group. For the second primary outcome, the infants who underwent prenatal surgery scored significantly higher (21 percent) than the infants who received traditional surgery.

In addition to evaluating the study results in terms of the two primary outcomes, the researchers also evaluated the results in terms of a number of secondary outcomes. Although the likelihood of being able to walk depends on the location of the spinal malformation, children in the prenatal surgery group were more likely to be able to walk without orthotics or crutches (41.9 percent) than were children in the postnatal surgery group (20.9 percent).

Hindbrain herniation, in which the base of the brain is pulled into the spinal canal, was present during pregnancy in all of the infants who participated in the trial. However, at 12 months of age, one-third of the children (35.7 percent) who had prenatal surgery no longer had any evidence of hindbrain herniation, compared to 4.3 percent in the postnatal surgery group.

"The findings suggest that the prenatal surgery allowed for more normal development of the nervous system and fewer complications," Dr. Spong said.

Children in the prenatal surgery group were more likely to be born preterm, at an average of 34.1 weeks of pregnancy, compared with the postnatal group, born at an average 37.3 weeks. In the prenatal surgery group, 20.8 percent of the infants had a breathing disorder associated with preterm birth (respiratory distress syndrome), which the study authors considered a consequence of being born preterm. For the postnatal surgery group, 6.3 percent had respiratory distress syndrome.

Mothers in the prenatal surgery group were also more likely to experience a thinning or tearing in the uterine incision used for the prenatal surgery procedure. In fact, one third of all the women in the prenatal surgery group had some degree of thinning at the time of delivery. The study authors noted that prenatal incisions in the uterus increase the risk for dehiscence or outright rupture during a subsequent pregnancy. They recommended that all women who undergo such surgery should be informed that, in future pregnancies, they would require a cesarean delivery before labor begins, to avoid the risk of the scar tearing open with the force of the uterine contractions.

The researchers added that the surgery might pose greater risks for categories of women excluded from the study because of health concerns. For example, severely obese women (body mass index of 35 or higher) were not included in the study because of the increased risk for complications of surgery. They noted, however, that obesity is common in women carrying a child with myelomeningocele. Maternal obesity is estimated to increase the risk of spina bifida 1.5 to 3.5 times.

"Experimental outcomes from animal studies and the results from this MOMS clinical trial suggest that prenatal surgery for myelomeningocele stops exposure of the developing spinal cord to amniotic fluid and thereby averts further neurologic damage in-utero," Dr. Adzick said. "Prenatal surgery also stops cerebrospinal fluid leak from the myelomeningocele defect which serves to reverse hindbrain herniation in-utero, and we believe that this in turn mitigates the development of hydrocephalus and the need for shunting after birth."

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends that all women of childbearing age consume 400 micrograms of folic acid, in a supplement or in a fortified grain product, to reduce the risk of having a child with a neural tube defect. The CDC recommendation is available at http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/00019479.htm. The CDC also provides information on spina bifida at http://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/spinabifida/index.html.

In 2009, an NIH study found that women with low levels of vitamin B12, found only in meat, eggs and other foods of animal origin, were at increased risk for having a child with a neural tube defect.

Information on sources of vitamin B12 and recommended daily allowances for the vitamin are available from the NIH Office of Dietary Supplements, at http://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/vitaminb12/.

###

The NICHD sponsors research on development, before and after birth; maternal, child, and family health; reproductive biology and population issues; and medical rehabilitation. For more information, visit the Institute’s Web site at http://www.nichd.nih.gov/ .

The National Institutes of Health (NIH) — The Nation's Medical Research Agency — includes 27 Institutes and Centers and is a component of the U. S. Department of Health and Human Services. It is the primary federal agency for conducting and supporting basic, clinical, and translational medical research, and it investigates the causes, treatments, and cures for both common and rare diseases. For more information about NIH and its programs, visit http://www.nih.gov .

BACK TO TOP

BACK TO TOP