Division of Extramural Research (DER)

Several organizational units within the DER support research on labor and delivery:

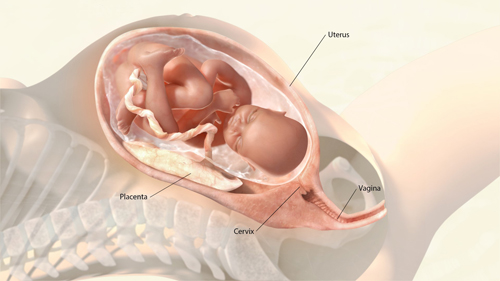

The Pregnancy and Perinatology Branch (PPB) seeks to improve the health of mothers and children by supporting research in several areas related to pregnancy, including labor and delivery. PPB-supported studies examine the development of the placenta and how it relates to labor and delivery outcomes; racial and ethnic disparities in preterm birth rates; adverse effects of oxytocin receptor desensitization due to prolonged oxytocin infusion during labor induction; molecular mechanisms of uterine contractions during normal labor, preterm labor, and post-term pregnancies; neural regulation of pre-partum cervical ripening; comparative effectiveness of antibiotics for cesarean delivery; development of improved labor diagnostic devices; obstetrical determinants of neonatal survival; and labor induction versus expectant management in post-term pregnancy.

- PPB-supported finding: Even a partial steroid treatment can improve survival and longer-term health among extremely preterm infants, researchers in NICHD's Neonatal Research Network found. A 48-hour course of steroids helps the lungs and other organs develop, improving survival for infants born at 22 to 27 weeks of pregnancy. But what a provider should do when not enough time is available to complete treatment before delivery has not been clear. After examining about 6,000 cases, the researchers found that mothers who received some treatment were more likely than those who did not to give birth to infants who survived, and their infants had fewer birth complications and developmental disabilities 1.5 years and nearly 2 years after birth. (PMID: 27723868)

- PPB-supported finding: When cesarean delivery is unplanned, adding a second antibiotic to standard measures to prevent infection could reduce infection rates by half. About 12% of women who undergo unplanned surgery to deliver their baby develop an infection. After studying more than 2,000 deliveries, researchers funded by NICHD found that 6.1% of women given the standard antibiotic treatment, cephalosporin, plus a second antibiotic, azithromycin, later developed an infection, compared with 12% of women receiving only cephalosporin. (PMID: 28076707)

The Obstetric and Pediatric Pharmacology and Therapeutics Branch (OPPTB) supports obstetric clinical trials, including studies of algorithms for simulation and new methods for using medical record data, and other research that can improve understanding of how to appropriately use pharmaceuticals during pregnancy, including medications commonly used during labor and delivery.

The Maternal and Pediatric Infectious Disease Branch (MPIDB) supports and conducts a wide range of domestic and international research related to the epidemiology, diagnosis, clinical manifestations, pathogenesis, transmission, treatment, and prevention of emerging infectious diseases such as Zika virus, HIV infection. MPIDB also supports and conducts research on infectious and non-infectious complications associated with HIV in pregnant women, infants, and the family unit as a whole. For example, MPIDB-supported researchers are investigating how tenofovir vaginal gel, a medication given during pregnancy, works to treat HIV and to prevent transmission of the virus from mother to child.

The Population Dynamics Branch supports research on demography, reproductive health, and population health. Current studies are examining the effect of mode of first delivery on subsequent childbearing and the role of prenatal employment in health care choices and services during childbirth.

Division of Population Health Research (DiPHR)

DiPHR conducts research to identify critical data gaps and designs research initiatives to answer etiologic questions or to evaluate interventions aimed at modifying behavior related to public health.

The Consortium on Safe Labor (CSL), led by researchers within the DiPHR's Epidemiology Branch, is an observational study whose goals are to explore the underlying causes of the high cesarean delivery rate in the U.S. population, describe contemporary labor progression at the national level, determine when is the most appropriate time to perform a cesarean delivery in women with labor protraction and arrest, and examine air quality and its effect on reproductive health and birth outcomes. The CSL includes 12 clinical centers and 228,562 pregnancies from across the United States. CSL research findings include the following:

- Compared with women who have a typical first-time pregnancy, women who attempt labor after a previous cesarean delivery experience a slower progression of labor, especially during the stages when the cervix dilates from 4 to 7 or 8 centimeters. A better understanding of the typical progression of labor could help providers better manage labor and delivery in a variety of circumstances. (PMID: 25935774)

- Women spend more time in labor now than approximately 50 years ago. The implication of this finding is that preventing cesarean delivery in the first pregnancy will go a long way toward decreasing the national cesarean delivery rate. Because providers are using definitions of "abnormal labor" developed in a population of women who are different from the contemporary obstetrical population, the CSL findings suggest that routine interventions, such as the use of oxytocin and timing of cesarean delivery, as well as modern-day labor process management, warrant reconsideration. (PMID: 22542117)

- A prolonged second stage of labor was associated with highly successful vaginal delivery rates but also with small increases in maternal and serious neonatal morbidity, as well as perinatal mortality in deliveries without an epidural. Investigators assessed neonatal and maternal outcomes when the second stage—the time from when pushing begins until delivery of the baby—was prolonged, according to American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) guidelines. The findings suggest that the benefits of vaginal delivery need to be weighed against the increased maternal and neonatal risks when second-stage labor lasts longer than described in the ACOG guidelines. (PMID: 24901265)

- Certain nonmedical factors are common in cesarean deliveries. Researchers using CSL data studied medical records from more than 145,000 deliveries involving a trial of labor. The baby was delivered by C-section in about 20,000 cases. The researchers analyzed the impact of factors such as when the delivery occurred, certain provider characteristics, the type of insurance used, patient characteristics, and policies at the institution. They learned that delivery in the evening, a male provider, a nonwhite mother, and use of Medicaid were associated with cesarean delivery. Understanding how these factors affect decision making about delivery could help with the design of ways to reduce high cesarean rates. (PMID: 23670226)

Other areas of ongoing research include determining the optimal time for the second stage of labor and exploring how sociodemographic changes in the current obstetrical population have affected pregnancy complications; maternal and neonatal morbidity; and implications for clinical management, including delivery timing and route. Researchers are also exploring how chronic diseases, such as hypertension, diabetes, and asthma, affect these outcomes. Further work from the CSL study will help shape the future clinical care of pregnant women.

Division of Intramural Research (DIR)

The Program in Perinatal Research and Obstetrics (PPRO) within the DIR conducts clinical and laboratory research on maternal and fetal diseases responsible for excessive infant mortality in the United States.

NICHD's research related to Preterm Labor and Birth is covered in the Preterm Labor and Birth topic.

BACK TO TOP

BACK TO TOP