- Hormone therapy

- Pain medications

- Surgical treatments

Hormone Therapy

Because hormones cause endometriosis patches to go through a cycle similar to the menstrual cycle, hormones also can be effective in treating endometriosis symptoms. Additionally, different hormones may alter our perception of pain.

Hormone therapy is used to treat endometriosis-associated pain. Hormones come in the form of a pill, a shot or injection, or a nasal spray.

Hormone treatments stop the ovaries from producing hormones, including estrogen, and usually prevent ovulation. This may help slow the growth and local activity of both the endometrium and the endometrial lesions. Treatment also prevents new areas and scars (adhesions) from growing, but it will not make existing adhesions go away.

Healthcare providers may suggest one of the following hormone treatments to treat pain from endometriosis:1,2,3

- Gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) medicines stop the production of certain hormones to prevent ovulation, menstruation, and the growth of endometriosis. This treatment sends the body into a “menopausal” state.

- A GnRH medicine called elagolix (also called Orilissa®) also stops the release of hormones to prevent the growth of endometriosis. It is the first pill approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to treat pain associated with endometriosis. Foundational research that led to the new drug was supported by NICHD through its Small Business Innovation Research program.4

- The low-dose pill should not be taken for more than 24 months and the high‑dose pill should not be taken for more than 6 months because it may cause bone loss.5

- The drug’s most common side effects include headache, nausea, difficulty sleeping, absence of periods, anxiety, depression, and joint pain.5

- Some GnRH medicines come in a nasal spray taken daily, as an injection given once a month, or as an injection given every 3 months.

- Most healthcare providers recommend staying on GnRH medicine for only about 6 months at a time, with several months between treatments if they are repeated. The risk for heart complications and bone loss can rise when taking them longer.1 After stopping the GnRH medicine, the body comes out of the menopausal state, menstruation begins, and pregnancy is possible.6

- As with all hormonal treatments, endometriosis symptoms return after women stop taking GnRH medicine.

- These medications also have side effects, including hot flashes, tiredness, problems sleeping, headache, depression, joint and muscle stiffness, bone loss, and vaginal dryness.

- Oral contraceptives, or birth control pills. These help make a woman’s period lighter, shorter, and more regular. Women prescribed contraceptives also report relief from pain.7

- In general, the therapy contains two hormones: estrogen and progestin, a progesterone-like hormone. Women who can’t take estrogen because of cardiovascular disease or a high risk of blood clots can use progestin-only pills to reduce menstrual flow.

- Typically, a woman takes the pill for 21 days and then takes sugar pills for 7 days to mimic the natural menstrual cycle. Some women take birth control pills continuously, without using the sugar pills that signal the body to go through menstruation. Taken without the sugar pills, birth control pills may stop the menstrual period altogether, which can reduce or eliminate the pain. There are also birth control pills available that provide only a couple days of sugar pills every 3 months; these also help reduce or eliminate pain.

- Pain relief usually lasts only while taking the pills, while the endometriosis is suppressed. When treatment stops, the symptoms of endometriosis may return (along with the ability to get pregnant). Many women continue treatment indefinitely. Occasionally, some women have no pain for several years after stopping treatment.

- These hormones can have some mild side effects, such as weight gain, bloating, and bleeding between periods, especially when women first start to take the pills continuously.

- Progesterone and progestin, taken as a pill, by injection, or through an intrauterine device (IUD), improve symptoms by reducing a woman’s period or stopping it completely. This also prevents pregnancy.

- As a pill taken daily, these hormones reduce menstrual flow without causing the uterine lining to grow. As soon as a woman stops taking the progestin pill, symptoms may return, and pregnancy is possible.

- An IUD containing progestin, such as Mirena®, may be effective in reducing endometriosis-associated pain. It reduces the size of lesions and reduces menstrual flow (one-third of women no longer get their period after a year of use).8

- As an injection taken every 3 months, these hormones usually stop menstrual flow. However, some women may experience irregular menstrual bleeding in the first year of injection use. During these times of bleeding, pain may occur.9 After a year of using the injection, about half of women report having no period. Additionally, it may take a few months for a period to return after stopping the injections. Even if a woman does not have a period, she may still be able to get pregnant; if pregnancy is not desired, a woman should take steps to prevent pregnancy.

- Women taking these hormones may gain weight, feel depressed, or have irregular vaginal bleeding.

- Danazol (also called Danocrine®) treatment stops the release of hormones that are involved in the menstrual cycle. While taking this drug, women will have a period only occasionally or not at all.

- Common side effects include oily skin, pimples or acne, weight gain, muscle cramps, tiredness, smaller breasts, and sore breasts. Headaches, dizziness, weakness, hot flashes, or a deepening of the voice may also occur while on this treatment. Danazol’s side effects are more severe than those from other hormone treatment options.1

- Danazol can harm a developing fetus. Therefore, it is important to prevent pregnancy while on this medication. Hormonal birth control methods are not recommended for women taking danazol. Instead, healthcare providers recommend using barrier methods of birth control, such as condoms or a diaphragm.

Researchers are exploring the use of other hormones for treating endometriosis and the pain related to it. One example is gestrinone, which has been used in Europe but is not available in the United States. Drugs that lower the amount of estrogen in the body, called aromatase inhibitors, are also being studied. Some research shows that they can be effective in reducing endometriosis pain, but they are still considered experimental in the United States. The FDA has not approved them for treatment of endometriosis.7

Pain Medications

Pain medications may work well if pain or other symptoms are mild. These medications range from over-the-counter pain relievers to strong prescription pain relievers.

The most common types of pain relievers are nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, also called NSAIDS.

Evidence on the effectiveness of these medications for relieving endometriosis-associated pain is limited. Understanding which drugs relieve pain associated with endometriosis could also shed light on how endometriosis causes pain.1,10

Surgical Treatments

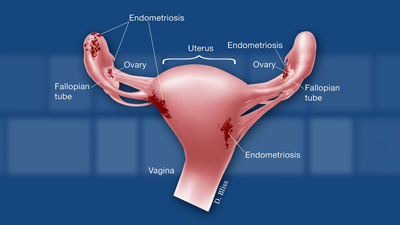

Research shows that some surgical treatments can provide significant, although short-term, relief from endometriosis-related pain,1 so healthcare providers may recommend surgery to treat severe pain from endometriosis. During the operation, the surgeon can locate any areas of endometriosis and examine the size and degree of growth; he or she also may remove the endometriosis patches at that time.

It is important to understand what is planned during surgery because some procedures cannot be reversed, and others can affect a woman’s fertility. Therefore, women should discuss all available options with their healthcare providers before making final decisions about treatment.

Healthcare providers may suggest one of the following surgical treatments for pain from endometriosis.1,2,10

- Laparoscopy. The surgeon uses an instrument to inflate the abdomen slightly with a harmless gas and then inserts a small viewing instrument with a light, called a laparoscope, into the abdomen through a small cut to see the growths.

- To remove the endometriosis, the surgeon makes at least two more small cuts in the abdomen and inserts lasers or other surgical instruments to:

- Remove the lesions, which is a process called excising.

- Destroy the lesions with intense heat and seal the blood vessels without stitches, a process called cauterizing or vaporizing.

- Some surgeons also will remove scar tissue at this time because it may contribute to endometriosis-associated pain.

- The goal is to treat the endometriosis without harming the healthy tissue around it.

- With surgery, most women have pain relief in the short term, but pain often returns. Surgery can provide long-term pain relief in women with deep lesions when those lesions are excised.1

- Some evidence shows that surgical treatment for endometriosis-related pain is more effective in women who have moderate endometriosis rather than minimal endometriosis. Women with minimal endometriosis may have changes in their pain perception that persist after removing the lesions.8,10

- Laparotomy. In this major abdominal surgery procedure, the surgeon may remove the endometriosis patches. Sometimes the endometriosis lesions are too small to see in a laparotomy.

- During this procedure, the surgeon may also remove the uterus. Removing the uterus is called hysterectomy.

- If the ovaries have endometriosis on them or if damage is severe, the surgeon may remove the ovaries and fallopian tubes along with the uterus. This process is called total hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy.

- When possible, healthcare providers will try to leave the ovaries in place because of the important role ovaries play in overall health.

- Healthcare providers recommend major surgery as a last resort for endometriosis treatment.

- Having a hysterectomy or salpingo-oophorectomy does not guarantee that the lesions will not return or that the pain will go away. There is still a slight chance that endometriosis symptoms and lesions may come back in some women even if they have a total hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy.1

- Surgery to sever pelvic nerves. If the pain is in the center of the abdomen, healthcare providers may recommend cutting nerves in the pelvis to lessen the pain. This can be done during either laparoscopy or laparotomy.1 The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) reports several clinical trials that showed these procedures to be ineffective at relieving pain from endometriosis. These procedures are not currently included in the ACOG recommendations for management of endometriosis.1,7,8

- Two procedures are used to sever different nerves in the pelvis.

- Presacral neurectomy severs the nerves connected to the uterus.

- Laparoscopic uterine nerve ablation (LUNA) severs nerves in the ligaments that secure the uterus.

In some cases, hormone therapy is used before or after surgery to reduce pain and/or continue treatment. Current evidence supports the use of an IUD containing progestin after surgery to reduce pain.8 Currently, Mirena® is the only IUD approved by the FDA to treat pain after surgery.

BACK TO TOP

BACK TO TOP