Reading Disability Expert Brett Miller Addresses Learning in Class, at Home, and in Science

Much of what we do in our early schooling and into our adult lives depends on being able to read, write, and do basic mathematics. Children with learning disabilities can face significant academic and emotional challenges as they struggle to master these skills.

Much of what we do in our early schooling and into our adult lives depends on being able to read, write, and do basic mathematics. Children with learning disabilities can face significant academic and emotional challenges as they struggle to master these skills.

Learning disabilities are caused by differences in brain function that affect how a person’s brain processes information. They are not an indication of a person's intelligence; people with learning disabilities are just as bright as other people. While learning disabilities can last a person’s lifetime, they may be lessened with the right educational supports.

Brett Miller, Ph.D., oversees the NICHD-funded research portfolio focused on learning disabilities. The program’s aim is to understand how children learn to read, write, and do math, why some children struggle so mightily to acquire these skills, and what can be done to help them.

In this video, Dr. Miller discusses learning disabilities research and what we know about how to teach children with learning disabilities.

Read the Dyslexia Research at NICHD text alternative.

An Early Interest in Education

What’s your professional background?

I’m a reading researcher by training. I’m interested in understanding how people learn to read and write, the problems people have with learning to read and write, and what can be done about those problems.

How did you become interested in reading and learning disabilities?

My mother was an educator and she placed a lot of importance on education when I was a child. As an undergrad, I worked in a lab that was focused on reading research. This work really gave me an opportunity to dissect the complex skill of reading, and I liked that. It also gave me the opportunity to help kids who have learning problems.

Do you talk about reading with your mother?

I do. She’s retired now, but we sometimes talk about instructional methods.

How common are learning disabilities?

Learning disabilities are one of the more prevalent disability conditions. It is estimated that between 12 [percent] and 20 percent of individuals have some type of learning disability. Dyslexia is the most common learning disability.

How do learning disabilities fit into the mission of NICHD?

The NICHD mission includes ensuring that individuals develop into healthy and productive people free from disease and disability, including learning disabilities. The mission also talks about rehabilitation for individuals who have a disability.

Teaching Children with Learning Disabilities

Could you give an example of NICHD-funded research on learning disabilities?

We have some recent results from a study that came out of our investment in the Learning Disabilities Research Centers. This study picked up kids at the end of fifth grade who were more than 1 year behind in their reading level. They were given explicit, systematic, and direct instruction in reading for 1, 2, or 3 years. That is, the children were directly and explicitly taught the component reading skills—including the rules of phonics—building their reading skill from the ground up. They also were given plenty of opportunity to practice their reading and to more generally enhance their understanding of the text.

Children who made good progress within the first year transitioned to less intensive interventions. Those who continued to struggle got a second year of even more intensive intervention: smaller group instruction, and more direct and explicit instruction. And those who continued to have difficulty went into a third year of intervention that was even more intensive than the first 2 years.

We found that the children who have 3 years of intensive intervention show really robust growth in reading comprehension and in word-level reading. And so this is a success story.

The flip side is that while we show these gains, we weren’t able to reduce the gap between the reading levels of these children and their peers. Their peers also continued to develop their reading skill, and so the gap remained.

So this study has implications for teaching children with learning disabilities?

This and other studies suggest that children with learning disabilities need direct, explicit, and systematic instruction, whether we’re talking about reading or mathematics.

These children will likely need more time to build their skills and receive instruction in smaller groups so that they get more focused attention—it can be a small group, it can be one on one—depending upon the needs of the child and how significant their learning challenges are.

We also know that our most efficient and effective interventions are for our youngest learners. Starting young helps reduce the impact the disability has on their broader academic development.

When should these interventions begin?

We know the risk factors when kids roll into kindergarten and even before that. For instance, if a parent has a learning disability, we know that the child’s at increased risk for having a learning disability.

If we know a child has a higher risk of having reading difficulties going into preschool or kindergarten, we can monitor them to see how they perform and give them very explicit, direct, and systematic instruction early on. Fortunately, this type of instruction not only benefits those who struggle, but it also benefits those who don’t, so it’s effective for all kids.

So it could be given within the context of the entire class?

Exactly, and that’s the hope and intent.

The Science of Learning Disabilities

What do brain imaging studies tell us?

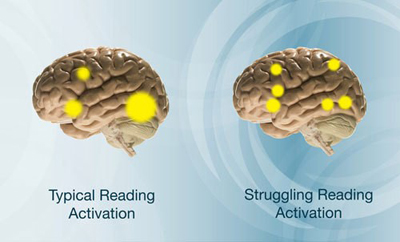

Brain imaging studies give us a window into understanding reading and reading disabilities. For the kids who develop typically with reading compared to those who don’t, we see more focal activation in areas on the left hemisphere of the brain and activation of parts of the left hemisphere that relate to improved word reading.

Kids who struggle with reading show more disperse activation in the left hemisphere. But if they successfully respond to a reading intervention, they show a brain activation pattern that looks much more like individuals who don’t struggle to read.

This is a remarkable example of what we call neuroplasticity; that is, you give an intervention in the classroom, and when the intervention is successful, you see changes in the structure and function of the brain.

Are there genes associated with learning disabilities?

Learning disabilities are complex conditions, and there’s no single gene that causes a learning disability or a reading disability. At this point, we’ve identified about nine dyslexia susceptibility genes. If you have one of these genes, it doesn’t mean that you’ll have dyslexia; it means that you’re at higher risk for having dyslexia. This is one piece of information that could help us ascertain who would be at risk for problems.

Are there new technologies to help people with learning disabilities?

There are a number of resources now that individuals with learning disabilities have available to them to help support their learning. For example, there is software that reads the book to you. There are efforts to have more books recorded. Recorded books have the benefit of reading that sounds more natural and with appropriate intonation, as opposed to the reading software. But it’s not practical to record every book, so reading will still be a necessary skill.

For individuals who have problems with writing, there are tools to help structure sentences and organize paragraphs and longer papers.

After Graduation

What tips do you have for parents to help their children?

If you’re a parent of a younger child, you can create a language-rich environment by talking with and reading with your child. This can help your child understand language structure—where to pause, how to allow someone else to talk— and improve his or her vocabulary.

You should read books to your child every day, giving them the story, vocabulary, background, and an understanding of how text is structured, how reading flows from left to right [in English], and how the pages are turned. You can ask children questions to encourage them to think about what you’ve been reading and what’s coming next in the story.

For children with a math disability [dyscalculia], you can point out numbers in your environment. When you’re going to the grocery store or doing everyday tasks, you can incorporate opportunities to learn about numbers. For example, where you see three apples, you can count them. You’re taking advantage of these opportunities to immerse your child in language and mathematical reasoning–rich environments.

For children in school, create a positive environment where you celebrate successes and work with the challenges. It’s important for parents to be role models who read and are engaged in their own lifelong learning. You can show children the calculations or measurements that you’re doing, like showing them how you do the bills or measuring length of objects with a tape measure. You can have writing activities like doing diaries, blogs, or other activities that are engaging and fun for your children.

What do we know about helping children who have learning disabilities achieve and thrive beyond school?

The skills that will help individuals with learning disabilities transition into adult employment or postsecondary education include knowing their challenges and being able to advocate for themselves to get the resources to succeed. In college, that might mean getting more time to take tests or getting software to read text more efficiently.

Are there personality characteristics associated with success that parents could help promote?

We talk about grit, the idea that you stick with it, that you persevere. The effort you put toward a task is going to be important in order to succeed.

And I think it helps to be lighthearted and to realize that everyone faces challenges in life and to stay positive.

BACK TO TOP

BACK TO TOP