Why Zebrafish?

Zebrafish are small tropical fish native to southeast Asia. They have a unique combination of genetic and experimental embryologic advantages that make them ideal for studying early development, particularly the embryogenesis of the circulatory system:

Zebrafish are small tropical fish native to southeast Asia. They have a unique combination of genetic and experimental embryologic advantages that make them ideal for studying early development, particularly the embryogenesis of the circulatory system:

Genetic accessibility

Adult zebrafish are small (approximately one inch long as adults), have a short generation time (3 months or less), and can lay hundreds of eggs at weekly intervals, making them amenable to large scale mutant screens. Thousands of mutants affecting many different aspects of early development have already been recovered from mutagenesis screens. The ability to collect thousands of progeny from a single pair of adult zebrafish also makes it easy to map mutations and cloned genes to less than 0.1 cM resolution.

Experimental accessibility

Unlike the embryos of many other vertebrates, externally fertilized zebrafish embryos are accessible to observation and manipulation at all stages of their development. This facilitates experimental techniques such as fate mapping, fluorescent tracer time-lapse lineage analysis, and single cell transplantation. We have pioneered additional novel experimental embryologic methods for studying the circulatory system, including confocal microangiography and multiphoton timelapse imaging of transgenic fish.

Unlike the embryos of many other vertebrates, externally fertilized zebrafish embryos are accessible to observation and manipulation at all stages of their development. This facilitates experimental techniques such as fate mapping, fluorescent tracer time-lapse lineage analysis, and single cell transplantation. We have pioneered additional novel experimental embryologic methods for studying the circulatory system, including confocal microangiography and multiphoton timelapse imaging of transgenic fish.

Optical transparency

The optical clarity of zebrafish embryos provides perhaps the greatest advantage for studies of vascular development. Every blood vessel in a living embryo can be seen using nothing more than a low-power dissecting microscope. One can easily visually screen for organotypic defects or analyze living embryos at single-cell resolution over long periods of time. The optical clarity and physical accessibility of zebrafish embryos also make this an ideal system to exploit the advantages of transgenic animals expressing fluorescent proteins such as EGFP and RFP/mCherry.

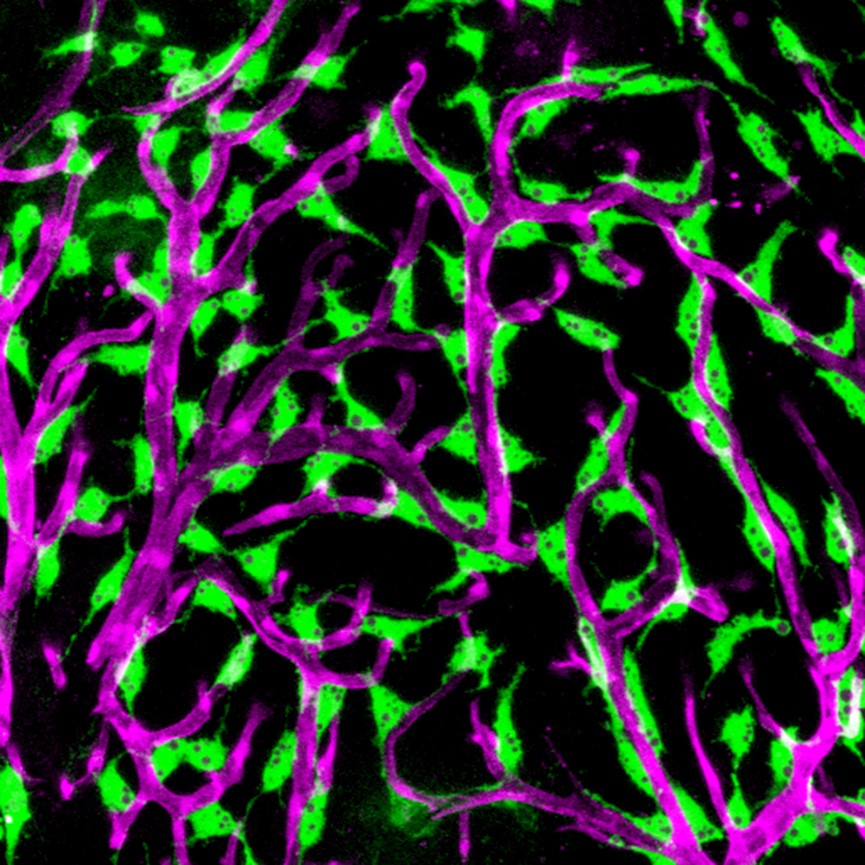

IMAGES: (ABOVE) Lateral views of adult male (top) and female (bottom) zebrafish. (BELOW) Confocal image of "fluorescent granular perithelial cells" (FGPs, in green) adhering to the outside of meningeal blood vessels (in purple) on the brain of a Tg(mrc1a:egfp); Tg(karl:cherry) double-transgenic adult zebrafish. The Weinstein lab recently showed that FGPs are unique endothelium-derived perivascular cells with unusual scavenging properties that are likely critical for brain homeostasis. See Venero Galanternik et al. for more details.

BACK TO TOP

BACK TO TOP