Reading is a complex, multipart process.1,2,3,4,5 View a slideshow that explains the process.

Spoken words are made up of smaller pieces of sound—called phonemes.

Spoken words are made up of smaller pieces of sound—called phonemes.

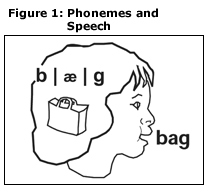

The English language has about 40 phonemes. When someone says a word, the sound comes out as one continuous stream (Figure 1). The brain must be able to separate the sound into pieces. For example, the word “bag” has three phonemes—/b/, /æ/, and /g/.

Understanding that words are made up of individual sounds is a key part of learning to read. An important skill that helps readers is called phonemic awareness, which refers to the ability to identify and manipulate (or work with) the individual sounds that make up a spoken word.

Phonemes make up spoken words, and words only make sense when these phonemes are combined in a particular order. Phonemic awareness can be taught and learned using activities such as rhyming games.

Another way to teach and learn this awareness is to work with single phonemes in spoken words, such as identifying the first sound in cat as /k/. Part of this learning is also realizing that a change to a single sound or phoneme can change the meaning of the word. For example, changing the /g/ in bag to a /t/ gives us the word bat, which has a different meaning from bag.

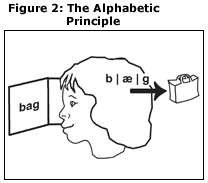

In alphabetic languages such as English, another part of learning to read is understanding that letters of the alphabet stand for sounds or phonemes. A phoneme can correspond to one letter or a group of letters. This knowledge is called the alphabetic principle (Figure 2).

In alphabetic languages such as English, another part of learning to read is understanding that letters of the alphabet stand for sounds or phonemes. A phoneme can correspond to one letter or a group of letters. This knowledge is called the alphabetic principle (Figure 2).

When students use the letter-sound pairings to sound out printed words, it is called phonics. This requires learning to pair their knowledge of the sounds in words (phonemic awareness) with their skill at recognizing letters.

To better understand phonics, think about how you read a made-up word like “blit” or “fratchet.” Even though you don’t know the made-up word or what it means, you can read it by figuring out what sounds the letters make. Then you can sound it out and pronounce it.

Phonemic awareness and phonics skills help readers sound out new words.

Knowing that a word has meaning is an important part of learning to read. The words we know are called our vocabulary.

Learning vocabulary starts very early in life. Infants and toddlers look at what you are talking about and say their first words to get what they need or want. As toddlers grow, they learn more and more words. By the time they start to sound out words to read, most children can recognize many of the words they are sounding out. They know they have heard those words before, and they know what the words mean. This is why having a good vocabulary is so important to reading.

As a reader continues to develop phonics skills, a specific reading skill called fluency also improves. Fluency goes beyond just pronouncing or knowing words. It includes many parts:

- Being able to read quickly

- Reading words accurately

- Saying words and sentences with feeling

- Stressing the right word or phrase so a sentence sounds natural and conveys the correct meaning

Understanding the information that words and sentences communicate is another important part of reading. This is called comprehension. Comprehension is the main goal of learning to read. There are many ways to improve comprehension:

- Building vocabulary. Readers with a bigger vocabulary can recognize more words and better understand the overall meaning of the text.

- Understanding the structure and organization of text. Readers who know what to expect can better comprehend what they are reading.

- Understanding different types of texts. Teachers can give students strategies or guidelines for understanding a newspaper, a fiction book, a textbook, or a menu.

Such strategies teach students to ask and answer questions about what they are reading, summarize paragraphs and stories, and draw conclusions from the information.

These skills are the foundation for understanding science, history, social studies, math, and the many other subjects students will study throughout their education.

Citations

- Berninger, V. W., Abbott, R. D., Vermeulen, K., & Fulton, C.M. (2006). Paths to reading comprehension in at-risk second-grade readers. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 39(4), 334–351. doi:10.1177/00222194060390040701

- Foorman, B. R., Breier, J. I., & Fletcher, J. M. (2003). Interventions aimed at improving reading success: An evidence-based approach. Developmental Neuropsychology, 24(2-3), 613–639. doi:10.1080/87565641.2003.9651913

- Richards, T. L., & Berninger, V. W. (2008). Abnormal fMRI connectivity in children with dyslexia during a phoneme task: Before but not after treatment. Journal of Neurolinguistics, 21(4), 294–304. doi:10.1016/j.jneuroling.2007.07.002

- Lyon, G. R., & Moats, L. C. (1997). Critical conceptual and methodological considerations in reading intervention research. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 30(6), 578–588. doi:10.1177/002221949703000601

- Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. (2019). National reading panel publications. Retrieved September 16, 2019, from https://www.nichd.nih.gov/about/org/der/branches/cdbb/nationalreadingpanelpubs

BACK TO TOP

BACK TO TOP