Endometriosis is a disease in which tissue similar to the lining of the uterus grows in other places in the body.

The word endometriosis comes from the word “endometrium”—endo means “inside,” and metrium means “uterus,” where a mother carries her baby. Healthcare providers call the tissue that lines the inside of the uterus the endometrium.

Researchers aren’t exactly sure what causes endometriosis, but some theories include the following:

- Retrograde menstruation. This theory proposes that endometriosis cells flow backward through the fallopian tubes and into the pelvis during menstruation.

- Coelomic metaplasia. This theory refers to a change in the characteristics of the cells that line the organs in the pelvis.

These theories don’t explain every instance of endometriosis, like endometriosis that occurs in organs such as the lungs (possibly due to spreading through the blood system or lymphatics) or the rare cases of endometriosis in men.

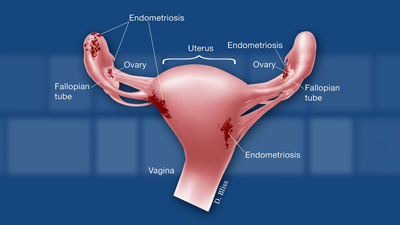

Healthcare providers may use the terms “implants,” “nodules,” or “lesions” to describe areas or patches of endometriosis. Most endometriosis patches are found in the pelvic cavity:

- On the ovaries

- On the fallopian tubes, which carry egg cells from the ovaries to the uterus

- Behind the uterus

- On the tissues that hold the uterus in place

- On the bowels or bladder

In rare cases, endometriosis may grow outside the pelvic cavity, such as on the lungs or in other parts of the body.1

Researchers’ understanding of endometriosis is changing with new scientific evidence. For example, researchers used to think that pain from endometriosis was related to the size of the patches growing outside the uterus. But evidence shows this is not the case. In fact, the size and location of the lesions are not related to the severity or to the location of the pain.2,3 Studies also indicate that pain is not associated with a woman’s ability to get pregnant.4,5

BACK TO TOP

BACK TO TOP